This piece reflects the personal opinions and thoughts of Jordan Macknick alone and should not be attributed to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory or the U.S. Department of Energy.

Two days after outlining an “all of the above” energy strategy in his 2012 State of the Union address, President Obama was in Colorado, driving this message home. It should be no surprise that President Obama came to Colorado to promote a diverse energy strategy; Colorado is rich in both fossil and renewable resources, and is likely to play an important role in a new energy economy. Domestic oil and gas production has been increasing and foreign imports have been decreasing, giving the U.S. its highest domestic levels of production since 2003— and this is likely to persist. Renewable-wise, Colorado has an aggressive Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) of 30% renewables by 2020, and has also been targeted by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) as an ideal location for expedited deployment of large-scale solar projects on Federal lands.

While this fossil and renewable energy development may be a boon to Colorado’s economy, creating thousands of jobs, what will be the long term impacts on Colorado’s water and land resources? Any energy development in Colorado is likely to be very water-intensive and land intensive; will a new energy economy in Colorado encroach on the agricultural landscape and water uses in Colorado?

In the Water-Energy-Land Nexus, researchers and policymakers are examining the tradeoffs inherent in supplying populations with water, energy, and food. Producing energy and food can be very water intensive. In addition, producing food and delivering freshwater to households can be very energy intensive. Lastly, some forms of energy production can be very land intensive.

In a changing climate, with potential impacts on the timing and quantity of available water resources, Colorado’s agriculture and energy sectors must be prepared to address uncertainty in their supply of water resources. We’re at an energy decision-making-crossroads, and we have lots of potential for different new energy sources, both renewable- and fossil-based, but no matter what we choose there are going to be tradeoffs.

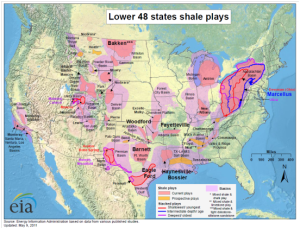

Colorado has substantial oil shale and shale gas deposits. Oil shale deposits are predominantly located in the northwestern part of the state, and shale gas deposits are located throughout the state. In 2010, shale gas comprised 23% of total U.S. natural gas supply. That could be a growing number– the Department of Energy’s Energy Information Administration (EIA) projects that by 2035 shale gas could constitute 49% of our supply. Oil shale is often extracted through mining and heating in above ground or underground activities. Shale gas is often extracted through a process called hydraulic fracturing. Both of these extraction techniques require water and can impact local land and water resources.

Federal agencies have already noted that large scale development of oil shale alone in Colorado could require more water than is currently supplied to residents in the Denver metro area. They also state that water used for oil shale operations could restrict agricultural and urban development—in fact, many holders of senior agricultural water rights have already sold their rights to oil shale companies. According to industry sources, hydraulic fracturing for shale gas can require, on average, 3 million to 4.5 million gallons of freshwater per well. In 2010, there were over 2700 new well starts for gas shale development in Colorado, and the Colorado Division of Water Resources expects the amount of water used for hydraulic fracturing in the state to increase by 35% over the next five years. The EPA has also released a draft report indicating that shale gas development in Wyoming may have contributed to local groundwater contamination. Although Colorado recently passed the most comprehensive and innovative chemical disclosure rules for oil and gas operations in the nation, further research is necessary to determine quantifiable water and land impacts of oil shale and shale gas development.

Solar energy resources are plentiful throughout the state, yet the greatest solar resource for photovoltaic (PV) and concentrating solar power (CSP) technologies is found in the southern part of the state, near the San Luis Valley. The BLM is looking to facilitate the development of large-scale solar projects in the San Luis Valley on BLM land; they have identified four areas totaling 16,000 acres for development in Colorado. Utility-scale solar projects can have a relatively large land footprint, with a 200 MW plant taking up around 2000 acres, or around 3 square miles. PV projects and some CSP configurations require only minimal amounts of water for cleaning solar collectors, yet other CSP configurations can require as much water for cooling as a nuclear power plant. A wet-cooled 200 MW CSP plant would consume as much as 420 million gallons per year to operate. Despite this relatively high water usage, a wet-cooled CSP plant still uses less water per acre than many irrigated crops such as alfalfa, fruit trees and cotton. One option to reduce this impact on water is to install CSP facilities with dry-cooling instead of wet-cooling technologies, but this may result in a larger land footprint in addition to cost and performance penalties.

Currently in Colorado, close to 86% of the water withdrawn is used for agriculture and 47% of the land is in the hands of farmers and ranchers. Thus any near-term development in energy will likely have a small impact on state-wide statistics. However, the local and county-level impacts on water resources and on agricultural land could be significant, and could drastically change the landscape and current way of life. Shale developments and solar developments are large and have lasting impacts, and citizens should know of these impacts when agreeing to allow developments to occur. Rural citizens and decision-makers are already having to decide whether they should be “growing megawatts” to feed the nation’s energy appetite or growing food crops to feed the state’s expanding population. Are local and state officials armed with sufficient information and resources to be making decisions about future energy and water developments in their regions? If not, what information and resources do they need to adequately make decisions?

This is a time when all Coloradoans could reflect on where we as a state are headed and where we want to be in terms of our energy, agricultural, and water resources. A coordinated energy-water-agriculture policy at the state level could help address the water and agriculture tradeoffs inherent in an expanding energy economy.

Jordan Macknick is an energy and environmental analyst for the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) in Golden, CO. His work there primarily focuses on the water-energy-land nexus.

Print

Print

Meanwhile, oil shale water requirements are a factor that can be turned on or off in the Portfolio Tradeoff Tool that the Roundtables are currently using to test their theories of how to balance water uses and tradeoffs in the future. Some Roundtables have been brave enough to turn off the oil shale button — thus freeing up 60,000 acre feet for other uses or to drop demand. The Colorado Basin Roundtable is not yet ready to take the bet that oil shale doesn’t lurk out there in the future. Sure, Chevron bailed on oil shale in Colorado, but Shell is still at work and some politicians are beating even harder on the oil shale drum.

Interesting point. For those of you interested in what the Federal Government is planning for potential oil shale development and associated land/water impacts for Colorado (and what that means for state/regional water planning), I recommend checking out the Oil Shale and Tar Sands Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) work happening right now (http://ostseis.anl.gov/index.cfm). Similar to the Solar PEIS, the BLM is evaluating potential development scenarios for oil shale on BLM land. For land use, the different oil shale alternatives for Colorado range from opening up about 27,000 acres of BLM land to opening up around 346,000 acres of BLM land.

The draft EIS was just published last month and the public comment period is now open until May 4th, 2012. If you are interested in what oil shale development means for Colorado’s land and water resources, I recommend reviewing the drat EIS and submitting your comments to the BLM. The EIS is long, but it is well organized and there are many detailed maps of basins and perennial streams that could potentially be affected. From my work with the Solar EIS, the BLM is required to read and take into consideration every single comment, so your voice will be heard!

You can read the EIS here:http://ostseis.anl.gov/documents/peis2012/index.cfm

and comment here:http://ostseis.anl.gov/involve/comments/index.cfm