TIME on the ancient Colorado River has stretched out for the people along its banks in spans so long it may as well have been infinite.

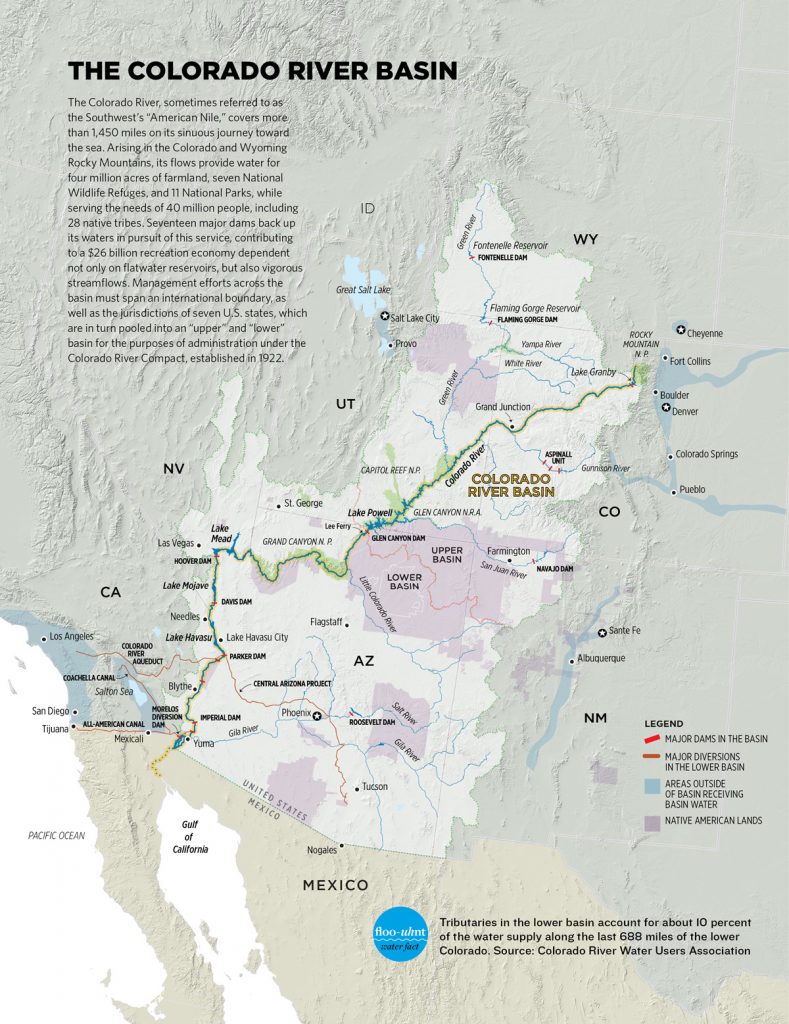

From Colorado to Mexico, to everyone from the tribes who reared their children in its mountain strongholds and fragile deserts to the modern city dwellers who have captured its vital flows in massive reservoirs and pipelines, the river’s troubled future has always seemed decades, if not centuries, away.

But time is speeding up in ways few modern-day water planners ever imagined. As a 16-year drought widely believed to be among the worst in 1,200 years shows little sign of easing, Lake Powell and Lake Mead—filled nearly to the brim in 2000—are now collectively less than half full and continue to fall, jeopardizing their ability to provide water to cities and farms, as well as to generate power, fund care for endangered fish, and support recreation economies worth billions of dollars each year.

Trouble is no longer decades or centuries away. Now, it could be perhaps a year or two away. “It’s come sooner than anyone anticipated and more significantly than anyone anticipated,” says Jim Lochhead, manager of Denver Water, the largest municipal water utility in Colorado. Even from the eastern side of the Continental Divide, opposite where the river begins its westward journey, the agency relies on the Colorado River for half its drinking water. “We are entering uncharted territory.”

No longer do states and water users talk exclusively about how much water they’re legally entitled to take. Now, they increasingly discuss ways to balance what they need with what the river provides, and they’ve begun to move forward with experiments designed to chisel away at decades of overuse in order to live on a water diet designed not by the courts or state legislatures, but by the river’s own highly variable flows.

A partially frozen Colorado River pictured in January 2009 cuts through Castle Valley, Utah. Photo by Pete McBride

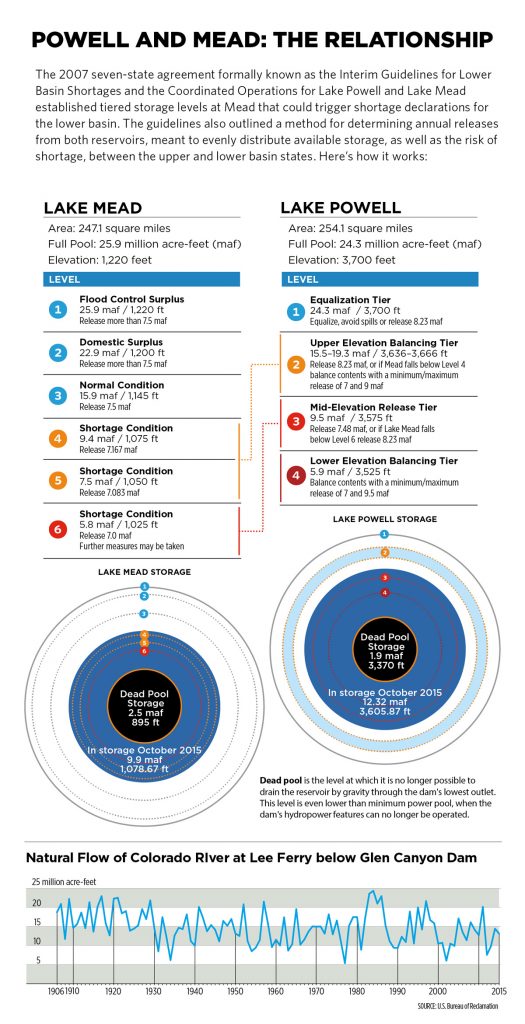

DROUGHT in the basin has materialized at different times and varying levels of severity since 2000. Often these periods of reduced precipitation and streamflows seemed short-term. The states managed by imposing mandatory water restrictions and tapping deep into reservoir storage. But by 2005 it was clear the dry periods were becoming increasingly severe and longer in duration. Water levels in Powell and Mead were dropping alarmingly. Conflict between the basin’s two U.S. halves—its lower and its upper basin states—came sharply into focus, causing the U.S. Department of the Interior to warn the states to come up with a new way to manage shrinking supplies and to balance storage between the two major reservoirs lest the federal government step in to do it for them.

It would take two years for all seven states to agree to a new management regime for Powell and Mead, a regime that said the upper basin states of Wyoming, Utah, Colorado and New Mexico could reduce their annual release from Lake Powell if it dropped below a certain elevation in order to better share the risk of diminishing supplies. The agreement also said that the lower basin states of California, Arizona and Nevada would implement staged reductions in Arizona’s and Nevada’s water withdrawals if Lake Mead falls below a series of defined tipping points.

In 2007, when what became known as the Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages and Coordinated Operations was finally adopted, planners remained optimistic that those tipping points might not be reached until closer to 2026, when the guidelines are set to expire, if at all. But the persistent drought combined with over-allocation of the river has drained the reservoirs faster than anyone predicted.

Flows across the basin in 2012 and 2013 were the lowest two-year period ever observed, raising particular alarm for the Central Arizona Project, which is subject to the greatest risk of water availability reductions in the lower basin under the unique priority system established by Congress nearly 50 years ago. Shuttling the vast majority of Arizona’s share of the river to farmers and cities in the state, the project delivers water to a region containing 80 percent of the state’s population through a 336-mile-long system of aqueducts, tunnels and pipelines. It is also expected to be the hardest-hit under the 2007 Interim Guidelines: The agency predicts a 55 percent probability that starting in 2017 its farmers will lose slightly more than half of the surface water they use to irrigate, and will have to replace those supplies with water that for years the state has cached underground for such a time as this. If the drought continues, its cities could face shortages in the very near future.

This year, heavy spring precipitation in the Colorado and Wyoming mountains meant that Lake Powell released a small surge of water, roughly 9 million acre-feet, up from the 8.23 million acre-feet it has released during “normal” years, dating back to 1970. And that is likely to give Arizona some breathing room. But if shortages don’t hit in 2017, most expect they will arrive shortly thereafter.

California, meanwhile, which gets nearly 60 percent of the lower basin’s share of the river, is facing its most serious modern drought. Last winter, the Sierra Nevada mountains delivered just 5 percent of their annual average snowpack. The water California gets annually from the Colorado River has been an invaluable water supply as the state scrambles to implement emergency conservation measures and to revise its laws and water management regime. Facing its own problems, California has thus far taken the position (grounded in the Congressional system set up in 1968) that it is enough for it to live within its legally allotted share of 4.4 million acre-feet per year. This it has managed to do for the last decade, after reducing its use of Colorado River water by 15 percent. Under various legal agreements, Congressional statutes and a U.S. Supreme Court decree, Arizona and Nevada will have to absorb the first lower basin shortages before California will have to cut back again. Yet that doesn’t mean California isn’t invested in bolstering the strength of the Colorado River system, averting lower basin shortages, and ultimately increasing the amount of water stored in Lake Mead, says Tanya Trujillo, executive director of the Colorado River Board of California.

For the upper basin states, in addition to localized water reductions already experienced as a result of the ongoing historic drought, they face the very real prospect of not being able to eventually utilize the full share they expect, if river flows continue to diminish and they must keep meeting legal obligations to the lower basin.

The Central Arizona Project captures and moves Colorado River water over 336 miles to serve an area containing 80 percent of the state’s population, including Phoenix and Tucson. Photo: Shutterstock

THE QUESTION of who gets how much water from the river is governed by the 1922 Colorado River Compact and 1948 Upper Colorado River Compact and a related set of laws, decrees and an international treaty collectively referred to as the “Law of the River.” It is within the bones of the original compact where part of the problem lies. The negotiators of the 1922 compact assumed the river could reliably deliver more than 17 million acre-feet of water each year, as measured at a point on the river 10 miles downstream of Lake Powell’s Glen Canyon Dam known as Lee Ferry, provided both Lake Mead and Lake Powell were constructed to store water in abundant years and even out low-flow water years. Gauge records from 1902, for example, showed there was only 9 million acre-feet available in the Colorado River that year, making storage necessary to implement the compact.

Rejecting some calls for a time-limited allocation, say for 50 years, the compact’s framers divided, in perpetuity, 15 million acre-feet equally between the upper and lower basin states, giving 7.5 million acre-feet to Arizona, California and Nevada, and 7.5 million acre-feet to the four smaller, less-developed upper basin states—Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming. Another 1 million acre-feet was allocated to the lower basin, including flows from tributaries that enter the river below Lee Ferry. The idea was to ensure that the lower basin states, which then and now have the most senior water rights on the river, could not take unlimited amounts from the river simply because they were growing faster than the other states.

Skeptical of the deal even back then, Arizona would take more than 20 years to ratify the 1922 compact. The 1928 Boulder Canyon Project Act further divided the lower basin’s share of mainstem water: California gets 4.4 million acre-feet, Arizona 2.8 million acre-feet, and Nevada 300,000 acre-feet.

But under the Colorado River Basin Project Act of 1968, which authorized construction of the Central Arizona Project, among others, Congress required Arizona to subordinate the priority of the CAP water supply to California in times of shortage. As a result, CAP has a lower priority than senior water users in Arizona, California and Nevada.

The upper basin’s share, though intended to be equal to that of the lower basin when established, was allotted with the provision that the upper basin states cannot cause the river’s flow to fall below 75 million acre-feet at the Lee Ferry gauge over any 10-year period, or 7.5 million acre-feet on average each year. Given the uncertainty over how much water the upper basin states would actually have left among them, they agreed in the 1948 Upper Colorado Basin Compact to divide their share on a percentage basis, with Arizona receiving 50,000 acre-feet and Colorado receiving 51.75 percent, Utah 23 percent, Wyoming 14 percent and New Mexico 11.25 percent of the remaining available water.

Migrant workers harvest lettuce grown with Colorado River water new Yuma, Arizona. Fields like this one, irrigated by water diverted from the Colorado, account for up to two-thirds of the fresh produce found in grocery stores across the nation during winter months. Photo by Pete McBride

Mexico in 1944 was allocated an annual 1.5 million acre-feet of the river’s flows by treaty with the United States.

In the decades after the 1922 compact was written, it became clear that the river was rarely able to generate more than 16 million acre-feet in any given year. Fast-forward to 2015, and the river has produced an average over each of the past 16 years of just 12.4 million acre-feet at Lee Ferry, according to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s natural flow database. This compares to a long-term historical natural flow of 16.4 million acre-feet. The situation has been buffered using the water stored in higher-flow years, largely in Lake Powell and Lake Mead. But neither has been full since 2000. Releases from Powell continue to routinely exceed inflows, and although the upper basin has so far been able to release the full amount required every year, the lower basin continues to withdraw far more each year than what is delivered to Lake Mead, causing that downstream reservoir to drop precipitously.

Several steps have been taken to help the states cope with rising anxiety over the declines in these massive storage pools, most notably the Interim Guidelines finalized in 2007. And it is those guidelines that dictate the shortages the lower basin states may soon begin to absorb, if the surface elevation of Lake Mead threatens to fall below 1,075 feet above sea level at the outset of 2017.

While Mead already dropped below 1,075 feet in June 2015 and continues to hover precariously low, it recovered some elevation before August, when Reclamation uses projections for first-of-the-year levels to make a shortage determination. As a result, no shortages will be implemented for 2016, and the states can catch their breath.

IN ADDITION to the existing over-allocation of the river, another “new,” major demand is likely to come from Indian tribes, some of which have established the right to divert significant quantities of water but have not yet developed the infrastructure to use it, and others whose water rights are promised but have yet to be formally quantified. The latter is the case for 12 of the 28 tribes in the Colorado River Basin.

In 1908, in a precedent-setting case creating what is known as the Winters Doctrine, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the establishment of Indian reservations implicitly and concurrently created tribal rights to river water necessary to support the reservation, predating the rights of settlers who arrived later. In many cases, however, tribes without water engineering records or adequate resources to pay for court cases and water projects have not yet been able to fully claim or develop their share of the river.

The situation improved in 1963 when the U.S. Supreme Court, as part of the Arizona vs. California decision, set guidelines for future quantification efforts. In 2014, Dan Cordalis, a tribal water right expert with the nonprofit environmental law firm Earthjustice in Denver, wrote “What we do know is that the 16 tribes in the basin that have quantified their rights have established the right to divert nearly 2.9 million acre-feet of water annually from the Colorado River system. It appears, therefore, the remaining tribal claims leave a significant ‘cloud’ over the certainty of existing non-Indian water rights and uses.” It is important to note that these reserved water rights don’t require that the tribes had an actual need at the time of the reservation’s establishment, but are instead based upon future uses of the reserved water.

A Reclamation study now underway in cooperation with the Ten Tribes Partnership, a coalition of tribes with Colorado River water rights, is working to determine how much water may be associated with those rights.

Yet efforts to quantify the tribes’ rights are much farther along than are efforts to quantify how much water the river needs to maintain its ecologic attributes in the face of the growing supply and demand imbalance. Add to that imbalance climate change and its potential impacts, which, as understood to date, could shrink the river’s flows by anywhere from 5 to 35 percent by the end of the century, and you have a significantly vulnerable system.

Lake Mead was created by Hoover Dam in 1935 on the border of Arizona and Nevada and serves as the main storage bank of the lower basin. Over the past decade, Mead’s water level has dropped an average of 12 feet every year, and as of October 2015, it was less than 40 percent full. Photo: Shutterstock

“The Colorado River is being used—precariously—beyond available supply,” says Jennifer Pitt, director of the Colorado River Project at the Environmental Defense Fund. “We’ve been able to fudge on this for a while because of the water we had in storage. But as climate change continues to manifest itself, impacts to the river itself will grow.”

In a vulnerability analysis published in 2012, Reclamation estimated the risk that ecological flows in the river basin will be impaired, or flowing below amounts targeted for healthy streams, stood at 38 percent when viewed 25 to 45 years out. On certain tributaries, that risk grew to 52 percent. The risks could be reduced if new management regimes are implemented—or supplies augmented.

In contrast, the risk that the availability of water taken out of the river for people and farms will be impaired is just 7 percent in the upper basin and 19 percent in the lower basin. Under various scenarios modeled by Reclamation, the vulnerability of water deliveries to cities and farmers could be reduced to as little as 2 to 5 percent, depending on which solutions are used.

But for the river itself, risks to environmental flows would only be improved slightly, down to about 30 percent on average basin-wide, regardless of which options are chosen to improve flows in the river, including reuse, desalination plants, better watershed management, and, perhaps most crucially, the use of water banks in the upper basin.

Under current law, the Endangered Species Act is the most powerful federal law protecting the ecological interests of the river. In addition, some stream segments flowing through national forests have legal flows that have been established and protected by the U.S. Forest Service. Several states also require some instream flows be protected in certain stream reaches. But Pitt says there are many places “where rivers may be imperiled that won’t be protected by the ESA. We need to work more on developing tools and agreements to protect those places, not just to avoid species extinctions, but to ensure we have healthy rivers to support nature and people.”

Another significant concern in the upper basin is that hydropower production at Powell could fall dramatically as reservoir levels decline. Glen Canyon Dam currently produces enough hydropower to supply 320,000 homes with electricity, providing an average of $150 million in wholesale power revenues each year. The concern isn’t just about how to replace the power itself, which is substantial, but also how to make up the revenue that would be lost. That money helps fund not only the operations and maintenance of Powell and other major upstream reservoirs, but also the basin’s salinity control program, the upper basin’s recovery programs for several endangered fish species, and the Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program. Without these programs, and the cooperative management they support to provide things like targeted flow releases to critical river reaches, invasive species removal, and hatchery-bred fish stocking, the federal government could be forced to consider shutting off water users, as it did in the Klamath River Basin more than a decade ago.

Environmental Defense Fund’s Jennifer Pitt helped negotiate the agreement that led to the 2014 pulse flow to the delta and was there to welcome the first water as it arrived from Morelos Dam. Photo: Yamilett Carrillo/Colorado River Delta Water Trust

TIME IS RUNNING OUT. For Arizona and Nevada, shortages are coming quickly. The lower basin states are rapidly approaching a crisis point, not necessarily because of drought or climate change, but because they already overuse the river by 1.2 million acre-feet a year, even under average conditions, according to Tom Buschatzke, director of the Arizona Division of Water Resources. The situation is referred to politely as “the structural deficit,” a collection of overdrafts and system losses due to evaporation, treaty-required deliveries, and contracted water uses at Lake Mead and downstream. This imbalance between water delivered into Mead and water going out has resulted in the reservoir falling at a rate of 12 feet per year or more, even when there is a “normal” release upstream from Powell.

The real shortages that Arizona could face as early as 2017 can be handled, Buschatzke says, by cutting water deliveries to farmers and halting the underground storage program Arizona has used for decades to protect itself against this moment in time. It has roughly 9 million acre-feet of water stored underground, much of it Colorado River water.

If water use doesn’t start decreasing, however, the situation becomes dire quickly and water managers up and down the basin are well aware that if Lake Mead drops below elevation 1,075 feet, the pain of the shortages will soon become everyone’s pain, starting first in the lower basin.

“It is the responsibility of all lower basin states and water users, and the United States, to take action to close the structural deficit….immediate action is needed,” said the Central Arizona Project’s “State of the River” report late last year.

Lake Mead reached 1,078 feet in mid-October, which marked the beginning of the 2016 water year, just three feet above the 1,075-foot mark that triggers the first set of reductions under the 2007 Interim Guidelines. With no relief in sight, water planners say there is little question that this is a defining moment on the river.

Jocelyn Gibbon, a Phoenix-based water attorney and natural resources consultant who tracks Colorado River management issues, says she believes people will look back on this time period “and either be grateful we made the choices we did, or they will look back and say we let everything crash.”

From his office in downtown Denver, some 100 miles from the Colorado River’s headwaters in Rocky Mountain National Park, Lochhead is tracking the speed at which the river’s health and its wet water supplies are declining.

Dillon Reservoir, Denver Water’s largest storage pool, has water rights so junior—dating back only to the 1950s—that it would be one of the first hit if the lower basin runs short of water and exercises its right to call for more. If that happens, 1.2 million people on Colorado’s Front Range could face water shortages, though how Colorado would administer curtailments under such circumstances is yet to be determined.

Lochhead calls this a scenario that has a “low probability of happening and a high consequence if it does.” As a 30-year veteran of Colorado River management and a participant in most of the recent major negotiations that have occurred over its use, he says he doesn’t know if things could have been done differently to bring the river back into balance. But there is one point he is quite clear on: “I never thought I would live long enough to have to deal with it.

Print

Print