If a new 2-cent tax was tacked onto that bottled tea, would you notice? What if there was a small tax on every liquid-filled container—water, tea, soda, all of it—sold in Colorado? Would you have the same reaction if your water bill increased?

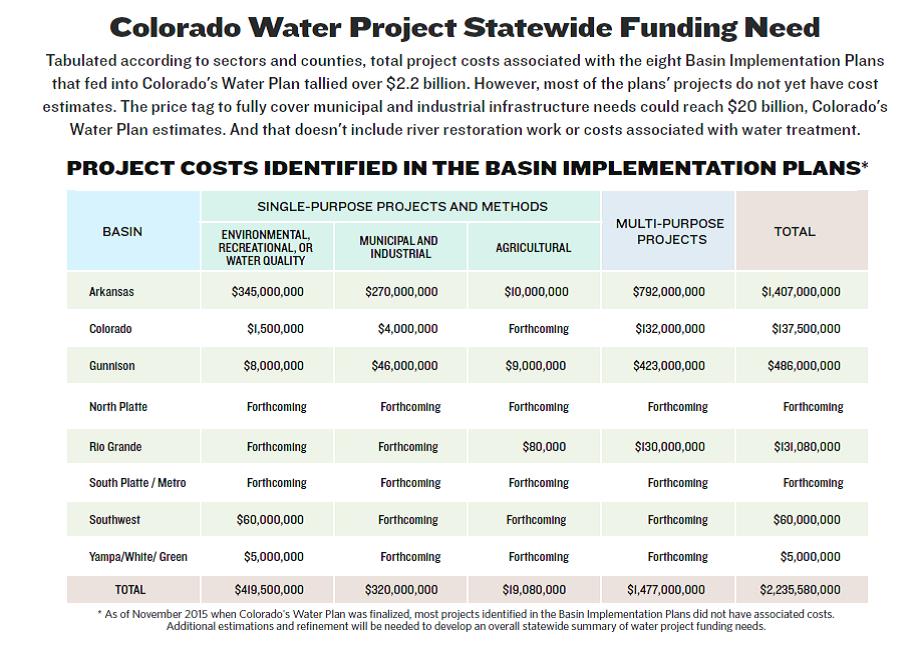

There are other options—but somehow Coloradans will need to come up with about $20 billion by 2050 for water projects across the state. The question is: How will we do it…and what will it mean for our bank accounts?

That $20 billion figure is what the Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB) estimates is necessary to implement Colorado’s Water Plan. The numbers aren’t exact, says Tim Feehan, former CWCB deputy director, and the specific projects and precise allocations aren’t completely set, but $20 billion is a starting budget as the state evaluates how the actions outlined in the water plan could be funded.

Aimed at addressing the municipal and industrial water supply gap so the state’s growing population doesn’t come up water short, Colorado’s Water Plan, published in 2015, also sets goals around alternatives to agricultural transfers, water infrastructure, storage, education, conservation, environmental projects, and recreational needs—plus it aspires to fund its own sustainable implementation.

“[The water plan] identifies a lot of solutions for the state and comes with a very high price tag,” says Margaret Bowman, a consultant working with the Water Funder Initiative to develop impact investing in the West. “Now the state’s got to figure out how to finance it.”

And the trouble is, the actual price tag is even higher than what’s outlined in the plan—Coloradans will have to finance that $20 billion and more. A higher sum will be needed for securing environmental and recreational needs as well as agricultural viability. Plus, that $20 billion doesn’t include treated water projects—drinking water, wastewater and distribution—which are all costly on their own. For context, the Colorado Water Resources and Power Development Authority has identified 377 projects on its drinking water needs list—valued at $5.4 billion—and another 305 projects on its wastewater list—for $4.6 billion.

But back to the initial $20 billion figure, which already sounds like an outrageous chunk of cash to many, that amount is divvied into more manageable sums that different entities will furnish in different ways for individual projects. The CWCB, for its part, sees itself in a complementary role, says Tim Feehan. “We’re there to make the process more streamlined—to fill in small funding gaps and help maybe with a little political will,” he says. Individual water providers and other project backers, whether pursuing water infrastructure, water supply, or water conservation, will be responsible for what the water plan’s Statewide Funding Committee, an advisory group of experts who work extensively in water and finance in Colorado, estimates to be 70 percent of that total—or $14 billion.

If the CWCB’s budget stays as it is in 2016, which is unlikely for at least the next two years while the state pays out severance tax refunds as a result of an April 2016 Colorado Supreme Court decision, it would have approximately $3 billion that could be used for loans and grants between now and 2050. That’s as much as $17 billion that can theoretically be accounted for, leaving an estimated $3 billion to be sourced through some new, creative, yet-to-be-determined initiative or funding source.

Colorado might have been two-thirds of the way there had a ballot measure, the Colorado Water Projects Bond Referendum or Referendum A, passed in 2003. The measure would have allowed the CWCB to borrow up to $2 billion for public and private water projects by issuing bonds, but it didn’t have a detailed plan outlining how and where the money would be spent, nor was there any new revenue to pay it back. “Everybody knew there was a need out there, but we [through the water plan] have spent the past 13 years trying to qualify it better,” Feehan says.

Now that that’s done, the state needs a new plan for generating the cash. And whether financed by the state or individual project backers, anything not philanthropically gifted through impact investing will still need to come from taxpayer funds or be borrowed and paid off, largely by Colorado water users through higher water rates and—yep—more taxes.

That’s where the container tax comes in, or any other idea with merit to distribute the costs across willing Coloradans. Broken down over the next 30 years, the $3 billion not yet accounted for is not an unreasonable sum: It works out to about $100 million a year. “Let’s say that we do need $100 million a year and there are 1 million households in the Denver metro area. That means each household would need to pay an extra $8.33 per month,” says Alan Matlosz with investment banking firm George K. Baum & Company and board treasurer for the Colorado Foundation for Water Education. Spreading that over the Front Range would cut that number in half—spread over the entire state it’s even less. That money could be distributed across the state’s grant making, loans, new green bonds, pilot projects, education and outreach programs, and other new items identified in the water plan.

Of course, that’s on top of increased water rates. “When you ask how you pay for [a water project loan], it directly goes to customers,” says Mike Brod, executive director of the Colorado Water Resources and Power Development Authority. Rate hikes to pay for projects will differ across the state, with some places having more affordable rates than others, just as some communities will have a greater need for water projects than others.

However not all customers—or communities—have equal ability to pay. Many smaller communities don’t have the revenue or ratepayers necessary to fund a major project.

In those situations, there are other options: steeper rate hikes, projects that may be covered in part by a grant, different loan structures, creative financing, or regionalized systems where costs can be spread across more water users. “I’m not worried about Denver finding a billion dollars to finance their projects, that should not be our concern,” Matlosz says, pointing to Denver Water’s high credit rating, old water rights, and huge customer base across which it can distribute its debt. “But,” he adds, “if there are big water needs in less urbanized areas, that’s trickier.”

When you combine rate increases with the $3-plus billion of new funding, possibly generated through taxation, plus the still-uncalculated treated water needs and wastewater needs, and look at all of that on top of other state funding priorities, it starts to add up. The cumulative result begs a larger question about priorities and how to determine the most necessary solutions that can be achieved affordably. Water is crucial, but so are public safety programs, human services, transportation, education, and other government spending areas. And water isn’t the only one in need of additional funding.

There’s about a $5 billion shortfall in state education funding today, ranking Colorado, the 14th richest state in the nation, 42nd in how much it spends per student; the Colorado Department of Transportation has only enough funding to maintain roads unless it can work out public/private partnerships, as was done on the U.S. 36 corridor; the economy is growing slowly; plus, the state’s TABOR limits, based on the Taxpayers Bill of Rights passed in 1992, cap property tax and income tax revenue to limit state government growth, leaving little money in the state’s general fund for new projects or to make up for these shortfalls.

The state’s Department of Natural Resources budget, which includes the Colorado Water Conservation Board, is only 1 percent of the state operating budget and 0.3 percent of the state’s general fund budget. “Those [general funds] are under constant pressure to fund growth,” says Bill Levine, budget director for the Colorado Department of Natural Resources. “There are many people who believe that there has not been enough in the general fund to meet the needs of a lot of the general fund programs.”

That’s problematic for a state that’s been working to accommodate a population growing by approximately an additional 8,000 people every month. Maybe it’s time to rethink how we invest in the future of Colorado. Everything has a cost. Can we come up with what’s needed? Are we ready to pay for what’s ahead?

Traditional Financing

There is an increasing need, but financing water projects and repairs on the state’s aging infrastructure isn’t all new. “Water and wastewater providers constantly need capital improvements,” says Alan Matlosz with investment banking firm George K. Baum & Company.

“Stuff is falling apart, rules change, and there’s population growth. [Water providers and municipalities] have to keep changing and adjusting, and they borrow a lot of money.”

Traditionally, water projects are thought of as tangible storage, treatment, and distribution needs that are bond- or loan-funded. Who provides the financing and how depends on the scope of the project and entity completing it, along with the parameters they’re looking to meet. For one municipality, water provider or project lead, it may be important to obtain the lowest possible interest rate, while another may need flexible loan terms or the fastest means possible of securing that money.

Loans

A water-related loan occurs under a scenario similar to any personal loan. A borrower approaches a lender to finance a project; if the project meets the lender’s criteria, an interest rate and repayment schedule is set and the lender issues a loan.

Most water loans in the state are issued at low interest rates through a state agency or quasi-governmental organization because many banks can’t issue a loan under the long repayment terms that water projects require. “Most community banks or local banks will only do business loans of about five to seven years,” says Brian Ervin, lead relationship manager with the water team at CoBank, a national lender and the only member of the Farm Credit System with the authority to lend directly to rural infrastructure customers. “In the water business, the assets have long lives, maybe 20-plus years, so it makes sense for water utilities and wastewater utilities to finance with long-term debt.” With most loans repaid over a 20- to 30-year period, the lifespan of the project, there are only so many options for borrowing.

The CWCB issues between $50 and $60 million in low-interest loans each year through its Water Project Loan Program, lending money from the agency’s Construction Fund and Severance Tax Fund for raw water projects around the state to agricultural, municipal and commercial borrowers. Interest rates range from 3.1 percent for high-income municipal loans to a low 1.7 percent for ag loans.

The Colorado Water Resources and Power Development Authority also issues between 20 and 40 low-interest loans per year, with interest rates between 0 and 2 percent, and loans averaging between $1 million and $5 million each and totaling $100 to $200 million annually, says Mike Brod, director of the authority. Authority loans go to municipalities and other local government entities typically in communities of fewer than 10,000 people to fund water and wastewater infrastructure development. That encompasses treatment, distribution, supply and collection.

Although the authority loans out higher sums than the CWCB, there could be a limit to its capacity. “We haven’t run out of money yet in terms of being able to make a loan, but there may come some day when we hit that point,” Brod says. That day would come if too many of the potential projects on the authority’s needs list seek funding at the same time.

The authority uses monies coming through two state revolving funds, the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund and Clean Water State Revolving Fund, to loan out and buy down their interest rates. That money is funneled into Colorado through the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and the authority provides a 20 percent match for every dollar that comes in, funded through bond issues.

Similarly, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Rural Development program as well as CoBank both lend money for water projects, with CoBank often issuing bonds to finance loans. The USDA issued rural utility funding to five entities in 2015, totaling just over $7.5 million in both loans and grants. CoBank hasn’t worked extensively in Colorado, as most municipalities seek lower-interest loans, but the lender has worked with USDA Rural Development on two loans where CoBank financed project construction, while USDA provided a long-term loan after construction. “Municipalities here [in Colorado] go to the State Revolving Fund,” Ervin says. “To my knowledge they’ve been successful in getting what they need from lenders.” But CoBank offers an option, particularly for small for-profit water companies, and issues water loans across the country ranging from $500,000 to $100 million. The lender offers market rates—slightly higher than the state offerings, with current rates around 4.5 to 5 percent—that can complement state grants and loans and are more accessible for certain borrowers. “CoBank is going to be much, much faster than the State Revolving Fund [loans offered by the authority],” Ervin says. Plus, the loan approval process is often easier and cheaper, he adds, because CoBank doesn’t always require so many steps, like environmental assessments, that can piggyback off a government loan.

The 8.5-mile Pleasant Valley Pipeline, completed in 2004, was built jointly by six northern Colorado water providers. Photo courtesy of Northern Water

Bonds

Municipal bonds have the same objective as loans—a municipality, water provider or special district wants to fund a project so they borrow money, only they create a bond and borrow from investors rather than one bank or agency. Issuing bonds can be an expensive endeavor involving consultants, advisors, attorneys and a bond underwriter who work with the bond issuer, create the bond issue and sell it to investors. Potential buyers analyze the municipality’s credit rating, the risk of investment, and the project itself. “The higher the rating on the bond, the fewer questions—but it all comes down to whether the interest rate is right,” Matlosz says. A borrower looking to issue a bond with a poor credit rating will pay higher interest rates—the risk is greater for investors so higher rates sweeten the deal.

Colorado Water Resources and Power Development Authority also issues bonds, with a bond issue limit capped at $500 million. The authority can create an issue by grouping various funding needs from numerous small municipalities, water providers, and other entities into one bond. “There are economies of scale to be had,” Brod says. For example, he’s working with Woodland Park to come up with $6.5 million and concurrently working with the City of Evans, which needs $42 million to finance a wastewater treatment plant. Pooling those needs into one bond issue creates a better deal for both entities and buyers—plus, those small municipalities benefit from the authority’s high credit rating.

The authority only issues a few bonds each year, while there are other water bond issues on the market much more frequently—regardless, there isn’t a cap on the quantity of bonds either can issue, as long as there is investor demand. “We do have a loan capacity,” Brod says. “But if we ran out of money on both [State Revolving Fund Loan] programs, I could still go out and sell bonds unrelated to those programs.”

When Borrowing Isn’t Easy

Traditional bonds and loans fall primarily under the water providers’ purview—theoretically they’ll comprise $14 billion of the $20 billion in needed funding identified in Colorado’s Water Plan. And though bonds and loans are the perfect funding mechanism for some projects, with no cap on how much they can bring in, some hopeful borrowers have a hard time accessing that financing. Whether a project is too small, too big or too risky, lacks political support or is not a moneymaker, grant funding, private investment, philanthropic dollars, and creative solutions may be able to move those forward.

State Grants and Funding

In addition to its lending authority, the state has some grant-making capacity. There are many different grant-making pools: Water Efficiency Grants; Water Supply Reserve Account Grants—the largest fund, authorized at up to $10 million per year; Watershed Restoration Grants; Alternative Agricultural Transfer Method Grants; Emergency Drought Grants, and many others, totaling around $25 million per year.

A small portion of the state’s grant making, about $4 million each year, comes out of its Construction Fund, but the majority of grants are made from the volatile and unpredictable severance tax pool. Severance tax is the tax on nonrenewable mineral extraction. Although it includes coal, metals and oil shale, between 90 and 95 percent of the severance tax revenue stream comes from oil and gas. Historically, Colorado has collected an average of $188 million in severance taxes each year, but the revenue stream is so volatile that it changes by an average of 86 percent from year to year, says Bill Levine, budget director for the Colorado Department of Natural Resources. In 2009 Colorado collected $319 million in severance tax. That amount dropped by 90 percent the following year to only $36 million—a massive dip, the likes of which occur regularly but still stymie economists’ attempts to make accurate predictions in order to inform budgets. Still, the state typically relies on that funding, splitting it evenly between the Department of Natural Resources and the Department of Local Affairs.

But a Colorado Supreme Court decision in April 2016 from BP America Production Company v. the Colorado Department of Revenue triggered changes, at least for the near future of Colorado’s severance tax revenue. The ruling broadens the deduction that oil and gas companies can claim against their severance tax liability, so moving forward the state will not only receive less severance tax revenue than usual, but must also issue refunds to accommodate deductions from the past few years. Those refunds will likely eliminate much of the CWCB’s current grant-making fund for the next year or two.

Creative New Funding

“If there’s a good project, it’s reasonable, and it can be paid back, then it can be financed by somebody,” says Alan Matlosz with investment banking firm George K. Baum & Company. “None of those projects will be unfunded.” Unfundable projects are often too expensive, speculative or risky.

For example, if a small rural community of 300 people wanted to build or update a water treatment facility to come into compliance with drinking water quality standards, the project would cost millions of dollars that the community couldn’t afford at any interest rate. It would instead have to look to alternatives to accomplish what was needed.

“I’ve never seen a system completely closed down. You absolutely go and find a way to get it done,” says Mike Brod, director of the Colorado Water Resources and Power Development Authority. Regionalization is sometimes a way for smaller systems to bring projects in reach. In other cases, project backers are finding private capital to be their best option.

Private Investment

“What we’re finding is there’s a lot of interest out there—there are billions of dollars looking to make investments in water, and they’re trying to find the vehicles best suited for their interest,” says Ben McConahey, partner with Hydro Venture Partners, speaking of private investment in the water arena. Investors have a growing interest and likewise can be attractive for water projects. The function of investors is similar to loans and bonds as they provide immediate capital or a needed service and make money back on their investment over time.

Hydro Venture Partners aims to solve some of the state’s water funding gaps and to platform strategies around water storage, supply and delivery, as well as energy and technology. Seeking capital primarily from wealthy individuals, family offices, and small institutional investors, Hydro Venture Partners earns money for its backers by investing in water projects.

“Our model can be a powerful vehicle for the private sector to have access to and make solid investments in water, a space into which the market hasn’t had much of this type of visibility,” McConahey says.

Private investment also presents an opportunity for those working to ensure Colorado is prepared for the future envisioned in Colorado’s Water Plan. “Everyone wants to prove that the work that went into the water plan can be executed,” McConahey says, expressing Hydro Venture Partners’ desire to help shepherd some elements within the water plan toward completion. McConahey believes private capital can offer some advantages to traditional water project financing, including private-sector expertise, accelerated delivery, and consolidation of resources.

Ben McConahey and his colleagues at Hydro Venture Partners have made it their business to usher capital investors into the water space. Photo by Theo Stroomer

That’s not to say that there aren’t barriers. Private equity investors actively analyze the level of risk in their investments and revenue sources, so deals have to be well structured to work. And the fear of privatization of public resources can lead to negative perceptions and challenging politics.

“We would love to prove that opportunities being identified aren’t just pipe dreams,” says McConahey. “There are feasible ways to mitigate the risk, deal with political, social and environmental factors, and ways to structure and provide solutions across different sectors of the community and benefit everyone involved. That’s our goal. To put together these opportunities where all the players can win.”

P3s

Public Private Partnerships, or P3s, similarly aim to share the responsibility of water projects between the public and private sector. The impetus for these projects, however, typically comes from an unmet need or new infrastructure needed by the public sector. From there, a private company can invest resources or offer its expertise as an investment. Although P3 models are common in transportation—a private company might front money or design and build a new road or bridge and then operate a toll to recoup its initial investment—they aren’t yet as popular in the water world.

“They’re not the same as transportation projects,” says Tim Feehan, former CWCB deputy director. “Water is a different monster. I don’t have to drive a turnpike if I don’t want to, but I don’t have a choice of who’s delivering my water. It gets sensitive on how we develop a model that works for water projects.”

Even so, P3s are listed as a possible funding option in Colorado’s Water Plan. The CWCB is focused on the potential for private capital in regionalized multi-partner projects and the Governor’s Office is supporting the effort by putting together a hub of experts who can analyze a project and determine where a water-based P3 might be logical.

Plus, as Colorado and the rest of the West builds its next round of infrastructure, it may need to rely on private funding to create the kind of sustainable, flexible infrastructure that’s needed, says Margaret Bowman of the Water Funder Initiative. “What we need is the next generation of infrastructure that’s more sustainable, recognizes the ecological system, and tries to work with that system not against that system.”

A new flexible and resilient infrastructure could include things like stormwater best management practices, watershed restoration projects, and projects typically thought to be outside the realm of traditional water project financing. “Unfortunately, the [public funding] rules are for traditional gray infrastructure. Whether you’re an environmentalist or not, you want the most responsive infrastructure there,” Bowman says. Gray infrastructure refers to distribution systems and traditional water or wastewater treatment. But for pilot projects, restoration work, and other less traditional water projects, private funding could be key. “[Public funding] is going to be important but it’s not going to be enough,” says Bowman. And that leaves philanthropic dollars.

Philanthropy

With the need for funding, heightened media messaging, and increased water scarcity in recent years, philanthropists, like many investors, have developed an interest in moving more money into Western water issues, Bowman says. In addition to the philanthropies that have been long supporters of water in Colorado like El Pomar, the Anschutz Foundation, and the Walton Family Foundation, others that have traditionally focused on economic development, early childhood education, public health, or the arts have started to realize water’s paramount importance. Nonprofits and projects seeking funding need to continue to make that pitch.

“A lot of [philanthropic] groups are funding healthy communities—it’s a really big topic right now and there are so many ways water fits into [it],” says April Montgomery, programs director with the Telluride Foundation and CWCB board member. “I think we need to change our dialogue a little bit.”

Montgomery helped convene a small group of foundations, businesses and water leaders in February 2016 with the goal of educating funders about the need to support Colorado water and the intersection of water across many interests. “We had a lot of great feedback,” Montgomery says, including word from many funders that they aren’t being approached about water. “There’s a need to be a little bit more creative and to pitch your issue in a different framework.”

For funders interested in making new investments in water, the Water Funder Initiative is helping guide that interest and those philanthropic dollars by outlining the broad issues and strategies that can transform the West into a more sustainable water environment. The initiative’s first move has been to compile a “blueprint” guide, published in March 2016, which lays out those initial strategies and critical, timely issues.

Although philanthropic investment doesn’t provide a huge pool of money, it isn’t insignificant. Colorado is home to more than 1,300 grant-making foundations; in 2013 they held more than $12 billion in assets and gave $803 million. That money can fund work that might not be possible otherwise, such as pilot projects, working through P3s, coordinating think-tank groups, and coming up with data to facilitate widespread transformation. “Philanthropy can convene people to deal with these things,” Bowman adds. “[It’s] a little bit of money that then can prompt broader private investment.”

Green Bonds

Some of those mission-driven projects that traditionally benefit only from grants and philanthropy could also be funded through green bonds. Green bonds, an idea that the funding committee hopes to actualize in Colorado, would mean the CWCB helping secure and provide private capital to environmental and recreational projects by selling bonds to investors at just-below-market returns. Once developed, that bond money could provide immediate funding for environmental projects.

Lacking either taxing authority or a reliable revenue source—and therefore the ability to issue traditional bonds—environmental and recreational projects struggle to finance their work. “You really are dependent on the largesse of granting foundations and individual donors,” says Ken Neubecker, with American Rivers—that is unless the environmental work is connected a municipal, industrial or agricultural benefactor’s project. Even the scale of need for environmental work is unknown because it’s underfunded. “There’s a lot we don’t know, and it costs money to find out,” Neubecker says.

A dedicated funding source would help. Still, details on green bonds for water in Colorado, including repayment cycles, have yet to be worked out. The water plan suggests that repayment might come from a combination of severance tax revenue or a new public initiative, such as a container fee.

Print

Print