In the Rocky Mountain state, where most water is already claimed, the Colorado River carries the last reserves of the life-giving liquid. But how much can safely be developed and at what cost?

Visit any ranch house in Colorado and there is almost always an expansive kitchen table and a wide picture window looking out over the home pasture. Wendy Thompson’s modest ranch house is like that. Backing up to Highway 9 just outside Kremmling, the house faces the hay meadows she irrigates each year. The Thompsons have operated this spread since they were newlyweds. They’ve reared two children here, the view from the picture window changing with the seasons, the coffee pot set in an almost-always-on mode for sisters, nephews, ranch hands and neighbors who gather at the kitchen table.

The ranch draws its water directly from the Colorado River. For years, the meadows flooded naturally in late spring, soaking in the clear, frigid snowmelt flowing down from the Never Summer Mountains. That changed after the late 1950s, when the Colorado-Big Thompson Project, the state’s largest transmountain diversion system, began taking about 230,000 acre feet of water to the Front Range each year. Now such flooding is rare.

In bad drought years, such as 2004, the river ran so low that the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District, which distributes Colorado Big-Thompson Project water, installed rock berms to raise the water level up to the irrigation structures that Thompson and other ranchers rely on. In a wistful moment, Thompson will tell you she would like to see those meadows flood on their own again, just to know the river had reclaimed some of its former self. “Our children are never going to see this area like it was,” she says.

Thompson spent her childhood on Troublesome Creek, just up the road. Grand County lore has it the creek was so-named for two reasons—old men died trying to cross and they battled endlessly over its supplies. The history of Troublesome Creek has played out again and again on the Colorado River, but never with so many people in the fight and so little water in the stream.

As Colorado faces an increasingly water-short future, it is looking at the Colorado River Basin to determine how much, if any, new water can be set aside and stored to meet the demands of a state population expected to grow from roughly 5 million in 2008 to between 8.6 million and 10 million in 2050. Colorado’s West Slope rivers, all of which feed into the larger Colorado River Basin, are the only rivers in the state that may still have water available to develop, a fact that makes Thompson and others nervous.

But it’s not just the Front Range that needs more water. Local communities along the Colorado River mainstem and its tributaries are expected to grow even more dramatically on a percentage basis during that same period, from 307,000 to between 661,000 and 832,000 within the basin’s six counties—Grand, Summit, Eagle, Pitkin, Garfield and Mesa—according to the Statewide Water Supply Initiative 2010. Local water needs for municipal and industrial uses are expected to more than double as well, from about 68,500 acre feet to between 130,000 and 180,000 by 2050. An acre foot of water is enough to serve about two urban households for one year.

The updated SWSI 2010 study, contracted by the Colorado Water Conservation Board and the state’s Interbasin Compact Committee, is a continuation of the effort the CWCB began in 2002 to determine how much water the state currently has available, how much it actually uses in its factories, farms and cities, and how much it will need by 2050. Since 2005, state-sanctioned community roundtables in each of the state’s major river basins have contributed to the effort by doing similar analyses at the local level. For example, an energy water needs study, recently completed by the Colorado and Yampa/White/Green basin roundtables, identified as much as 120,000 acre feet of future water demand for a growing energy industry in the state’s northwest corner.

Statewide, Colorado will need between 600,000 and 1 million acre feet of new water by 2050, including energy-related demand. That number factors in 150,000 acre feet of water expected to be freed up through so-called passive conservation if water-saving appliances are mandated for new construction. Approximately 350,000 acre feet could be supplied through projects that are already planned or underway, assuming a somewhat optimistic 70 percent success rate—and additional development of Colorado River Basin water.

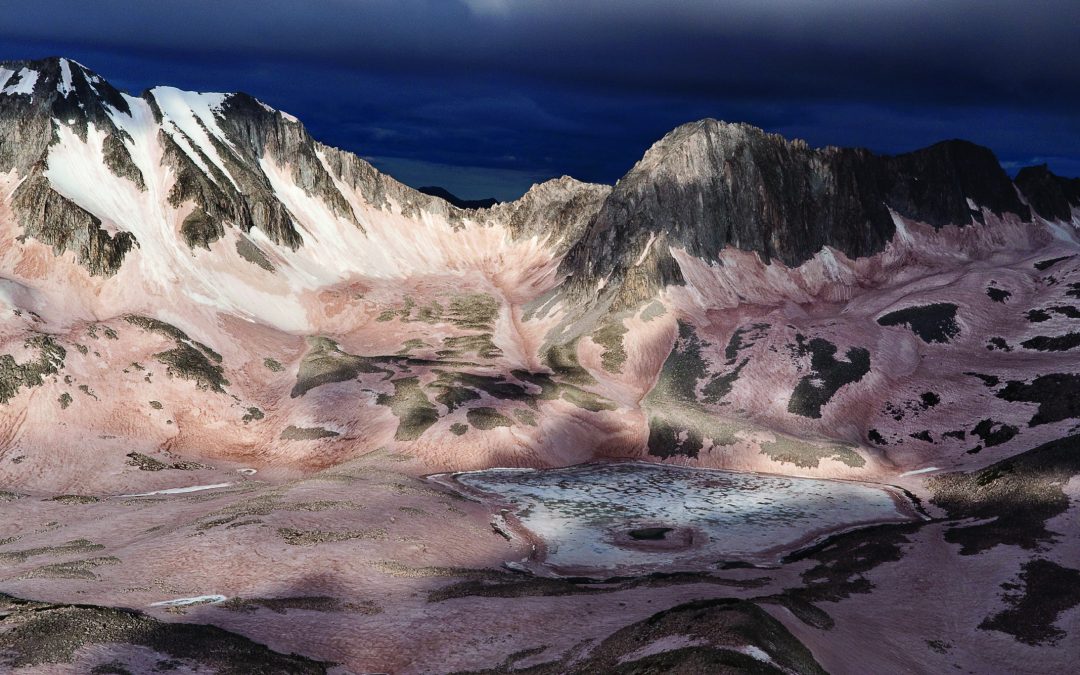

The Colorado River looks modest as it flows through Kremmling, Colorado, but it supplies more water than any of the state’s other rivers. Photo By: Kevin Moloney

The Last Increment of Water Development

How much more water is really available for the state to draw from the Colorado River Basin on a reliable basis is still a fairly open question. The Colorado River Water Availability Study, conducted by the Colorado Water Conservation Board, has concluded preliminarily that somewhere between zero and 900,000 acre feet may still be available annually, depending on climate change and how various rules in the 1922 Colorado River Compact and subsequent agreements are interpreted. It’s a wide range, and there are more questions than answers.

“There is no more conventional wisdom about how much water is left to develop,” says Eric Kuhn, general manager of the Colorado River Water Conservation District. “The most prevalent answer to the question is that we don’t know.” Before the drought of the early 2000s, Kuhn says most people believed Colorado could develop at least some additional water because it was only using about 2.6 million acre feet of the roughly 3.8 million acre feet it could take while still fulfilling downstream obligations under the 1922 compact and the Upper Colorado River Basin Compact of 1948. “The safe number we thought we could develop was about 400,000 to 500,000 acre feet.”

But climate change projections are throwing those already tentative numbers up in the air. A gradual warming could lower flows by 10 to 30 percent. Even a 10 percent reduction, coupled with the fact that the river already doesn’t produce as much water as its users are legally entitled to—as a 2007 hydrologic study by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation concluded—would make a 250,000 acre foot diversion project, such as those Front Range utilities have discussed, risky. If warming steals 30 percent of the river’s flows, it would catapult the whole system into crisis, leaving Colorado with less water now than it has historically used, according to a new report by the Western Water Policy Center at the University of Colorado entitled “Rethinking the Future of the Colorado River.”

“It’s going to be a banner year, a recovery year. It’s good news for now, but it could get dry again.” – Ted Kowalski

At the same time, the river is having difficulty keeping Lake Powell and Lake Mead at their historical levels. Lake Powell is the primary water bank for the upper basin states of Wyoming, Colorado, Utah and New Mexico. Water stored there ensures that even in dry years, the upper basin can meet its obligation to the lower basin—Arizona, Nevada and California. Since 1999, however, Lake Powell has dropped from 97 percent full to 53 percent full as of May 2011. And it is only due to balancing guidelines adopted by all seven basin states and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in 2007 that Lake Mead’s levels are approaching the 50 percent-full mark. In an April 2011 press release, Interior Secretary Ken Salazar said, “Drought conditions over the past 11 years had raised the possibility of water shortages in the lower basin over the next year, but thanks to good precipitation, wise planning and strong collaboration among the states, we are able to release additional water and avert those shortages.” Reclamation’s plan, as of April, was to release an additional 3.3 million acre feet of water to Lake Mead from Lake Powell, which is expected to receive 159 percent of average inflow this year. According to Ted Kowalski, chief of the Colorado Water Conservation Board’s Interstate and Federal Section, the additional release planned from Lake Powell rose by another 1 million acre feet after April and May continued to yield remarkable precipitation. “It’s going to be a banner year, a recovery year,” says Kowalski. “It’s good news for now, but it could get dry again.”

Additional water development in Colorado could potentially put the state in a position where, on a regular basis, it is no longer able to meet its compact obligations—at least not without requiring some water users to discontinue diversions. That risk is being weighed against the alternative of forgoing the Colorado Basin as a source for new water, especially for the Front Range. Many state water officials and utility managers believe Colorado must fully develop whatever may be left of its compact apportionment in the river to protect its water future. “The water users within the state of Colorado need to figure out how to develop that compact entitlement safely and reliably to maximize the beneficial use,” says Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District general manager Eric Wilkinson.

Bracing for a Tight Water Future

Several major transmountain diversion projects have been discussed during the past decade. Most of these are still simply plans on paper, with few firm water rights or legal water court decrees ready to go. These projects were analyzed for water yield and cost by the latest SWSI study. What’s known as the Flaming Gorge Pumpback would pipe Green River water from Flaming Gorge Reservoir in northeastern Utah all the way across southern Wyoming to deliver it to the Front Range. Another competing project would take water from the Yampa River near Maybell and pipe it across northern Colorado, again for delivery to the Front Range. Still another project would pump water back from the Gunnison River Basin from Blue Mesa Reservoir.

“No one really knows how climate change will impact the basin … Our hope is that we can get ahead of the crisis and develop solutions for managing the river in an adaptive way.” – Taylor Hawes

Assuming one project was built to deliver roughly 250,000 acre feet of water—a figure some consider too high but others think is realistic—the price tag would run between $5 billion and $9 billion, according to the SWSI study, roughly the cost to build one or two more Denver International Airports. How such a project would be financed isn’t clear yet, although the project’s beneficiaries would likely have to pay for it via increased water rates and taxes. And although none of these projects would develop water directly from the Colorado River mainstem, they would affect future in-basin water development by eating up much of what could still safely be developed under the terms of the compact.

The possibility that drought, climate change and the phenomenon known as “dust on snow”—where dust-coated mountain snowpacks absorb heat and melt faster—may drastically reduce in-state flows weighs heavily on the minds of policy makers. “No one really knows how climate change will impact the basin,” says Taylor Hawes, director of The Nature Conservancy’s Colorado River Program. “The promising part is that it has gotten the people’s attention and the attention of policy makers, decision makers and leaders. Now there is an awareness that we need new ways of managing the river that reflect the fact that we may have less water and increasing demands. Our hope is that we can get ahead of the crisis and develop solutions for managing the river in an adaptive way.”

Dick Wolfe, Colorado State Engineer, is likely to be the administrator who would be forced to rule on which water users are shut down if there were a curtailment where Colorado was legally required to use less water in order to meet downstream compact obligations. “You can imagine the complexities,” says Wolfe. He anticipates the rule-making process alone—which won’t start until the Colorado River Water Availability Study is completed sometime in 2011 or 2012—will take three years.

Water planners are also preparing for a potential curtailment by studying the creation of a West Slope water bank. West Slope irrigators with pre-1922 water rights could fallow a portion of their farms and store their unused water for use by West Slope or Front Range utilities if those utilities are forced to shut down. Farmers would be paid for their water and have the ability to use it again when the river’s flows were higher. “A water bank could act as broker, as a temporary exchange of water rights,” says Hawes. “Our hope is that we would have a year or two of warning so that we could fallow these rights in advance.”

Balancing Future Water Supply Needs

If Colorado and its namesake river have never faced so many challenges, never have so many people been working cooperatively to reshape how the river’s supplies are doled out. Jennifer Gimbel, executive director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board, tracks almost every water study underway. “Now we have better information and better tools to analyze possibilities for the future than we ever have before,” she says. “And we have the Interbasin Compact Committee, where people are actually talking about this rather than ignoring it.”

The IBCC was established in 2005 to facilitate water supply discussions between Colorado’s eight major river basins and metro Denver area. The group is also being used as a sort of think tank to help Gimbel and the CWCB develop water policy. Currently, three of the nine gubernatorial appointees on the CWCB’s board of directors are also part of the 27-member IBCC. The most recent CWCB board addition is none other than the man who conceived the IBCC in the first place, Russ George.

There is some consensus from the IBCC, Gimbel says, that any approach the state takes must look concurrently at conservation, re-use, non-permanent farm to city transfers, completion of existing projects and new water development. But even as the IBCC and CWCB work to plot a strategic and agreeable path forward, individual water providers continue moving to secure scarce water supplies.

Denver Water, the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District and the Colorado River District, along with county governments, irrigation districts and watershed groups, have been diligently working to resolve various disputes surrounding Colorado River Basin water, knowing that without definitive action in the next three to five years, shortages are possible. “We’ve been in negotiations with the West Slope for the past several years on an agreement that deals with a number of different issues, from Grand County to the Grand Junction area,” says Denver Water’s manager Jim Lochhead. The terms of the tentative Colorado River Cooperative Agreement benefit the West Slope by buffering streams during periods of low flows and supplementing its future water supply, but also pave the way for Denver to divert more from the headwaters during high flow periods.

While Denver Water awaits permits on a project that will take an additional 10,000 acre feet each year from the Fraser and Williams Fork rivers in the Colorado Basin—plus 5,000 acre feet annually via its other system on the Blue River—and deliver it through the Moffat Tunnel into Gross Reservoir in Boulder County, the Municipal Subdistrict of the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District is doing the same for the Windy Gap Firming Project. That project would add an average of 30,000 acre feet—over 2003 conditions, when the permitting process began—to diversions from the headwaters of the Colorado each year. The water would be pumped up to Granby Reservoir and through the Adams Tunnel to a proposed, new reservoir called Chimney Hollow for cities such as Loveland and Broomfield.

Grand County manager Lurline Underbrink-Curran, who has spent more than 25 years negotiating thorny water issues with the large Front Range water providers who rely on the county’s rivers, says she is pleased with the level of cooperation Grand County is seeing from Northern and Denver Water. She believes that the two water providers’ current efforts to improve water quality and streamflows will determine how the West Slope will respond to any future efforts to develop more water out of the Colorado River.

Her colleagues on the Front Range understand this and appear committed to shifting the way they do business. Says Lochhead, “It’s a true partnership in terms of how we move responsibly into the future, how we deal responsibly with the environment and the economies of everyone we deal with.” Northern, looking for ways to win the federal permit for its Windy Gap project, is also actively negotiating with Grand County to improve water treatment and streamflows and to provide additional storage in Windy Gap for the Middle Park Water Conservancy District, which serves small communities in the Fraser and Williams Fork region of Grand County.

Windy Gap, coupled with future projects Northern Water hopes to do with water from the Cache la Poudre and the South Platte rivers, should take care of the district’s growing needs, Wilkinson says. “We don’t anticipate going to the Colorado River for more water. But we’re hoping the state will find ways to fully develop our compact entitlement. If that is not done, there is going to be a commensurate impact on irrigated agriculture, particularly in the South Platte Basin. For every acre foot of compact entitlement that we can develop, it will mean an acre foot that won’t come out of agriculture.”

Managers in the Colorado River Basin share a sense of urgency regarding future development of the river for their own needs. Growing communities, such as Grand Junction, are forecasting dramatic jumps in water demand during the next 35 years. Steve Ryken is assistant manager of the Ute Water Conservancy District and sits on the Colorado Basin Roundtable. Ute, which serves about 80,000 people in the Grand Valley, expects to need an additional 21,000 acre feet of water by 2045, up from the 15,000 acre feet it currently uses. Ryken said his district has spent roughly $1 million during the past eight years laying the groundwork to expand a nearby reservoir. “There is no guarantee, given federal permitting requirements, that anything will ever get done,” Ryken says. So he is hopeful the state will move to protect whatever may be left of Colorado’s share of the river. If that entitlement isn’t developed, Ryken, like others, believes that agricultural water will continue to be purchased and transferred to municipal use.

“We’re going to have to recognize that the river has limits.” – Taylor Hawes

The SWSI 2010 study indicates that statewide, Colorado could lose 15 to 20 percent of its irrigated farm land by 2050 due to urbanization and water transfers to supply municipal needs. The mainstem Colorado River Basin could lose as many as 77,000 acres, or 29 percent. With shrinking farm economies, the rural ranching culture that has historically shaped the West Slope will fade.

Hawes, like others, believes Colorado is on the verge of a series of major breakthroughs in water management that may serve as models for the rest of the region, but these breakthroughs will come at a cost. “We do believe we can manage the river to meet everyone’s needs, but we are not going to be able to support as much agriculture,” she says. “We’re also probably going to lose some rivers.”

Some streams, for instance, like the Gila in New Mexico and Arizona, once flowed year round but are now only intermittent. Hawes believes this will occur more often with other streams as well, as population growth, climate change and drought continue to take their toll. “The question is, ‘Can we prioritize the places that are too important to lose? And are there agricultural areas that are too important to lose?’ The tradeoff on the municipal and industrial side is that we’re going to have to be more efficient and to be more careful about land-use decisions.”

Ultimately, she says, “We’re going to have to recognize that the river has limits.”

This is something that ranchers like Thompson have known for decades. If she could wave a magic wand, Thompson would advocate for minimum streamflows for the river that current water rights holders help support. Donating a portion of a valuable water right to protect the stream is a fairly radical idea in Colorado, where such minimums have typically come about only under pressure from the state or the U.S. Forest Service and which require expensive, complex water court cases to finalize.

But Thompson says it is time for everyone to sacrifice in order to protect the river for generations to come. “I think the river needs a minimum flow. In a drought, that’s tough. But everybody who has water rights should be willing to do something.”

Print

Print