We live in a time of what Martín Carcasson calls “wicked problems.” We’ve all seen them—political standoffs in D.C., heated dialogue on topics like hydraulic fracturing, and don’t forget Colorado’s first-ever recall elections in September 2013 over gun control disputes. As a society, we’ve become polarized.

According to Carcasson, who directs Colorado State University’s Center for Public Deliberation, these issues exist because of our competing values, attitudes and preferences. As important as scientific research is for developing solutions, we can’t research these kinds of differences away, Carcasson argues. Instead, leaders need to deliberately engage the public in talking through issues.

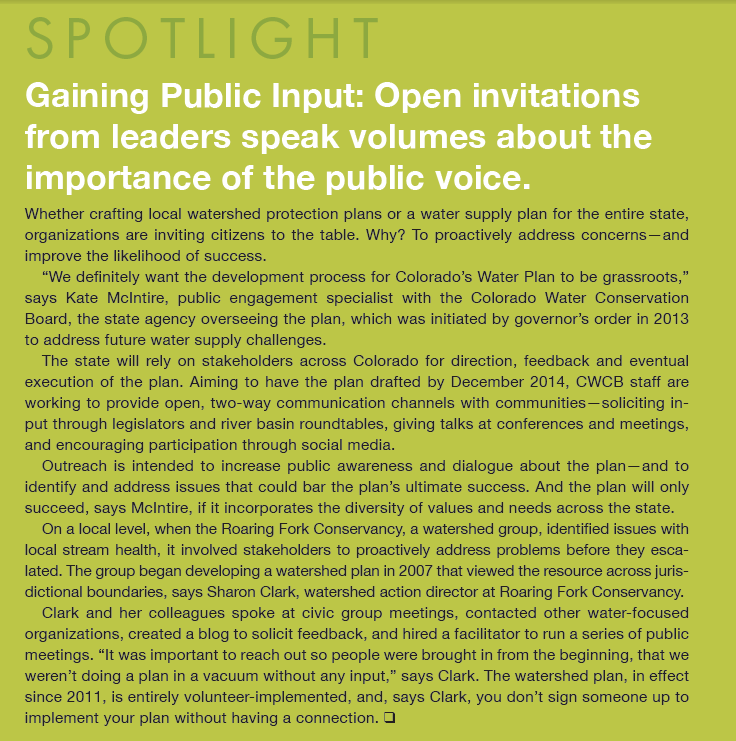

Government officials, scientists and stakeholders (top) discuss issues facing the Roaring Fork River during a Watershed Summit hosted by Roaring Fork Conservancy in 2010. Former state Rep. Kathleen Curry (above) speaks at the summit. Photo By: Greg Poschman

MaryLou Smith, professional facilitator with the Colorado Water Institute, leads dialogue around tense water issues and says the process can take years to produce solutions. That is in part due to human nature. “If we could get people to start listening more deeply to one another, to have an attitude of wanting to resolve something, to make it work broadly instead of wanting to win…we

could change the culture overnight,” says Smith.

The goal for facilitators is to help people find common ground and agree on next steps like legislation or formal solutions that account for everyone’s concerns. However, extensive public engagement may not be possible for every problem, says Connie Lewis, senior partner at the Meridian Institute. “Not everyone can afford it, in spite of the fact that a penny spent now may save a penny later,” says Lewis. The investment could stave off legal battles or other forms of opposition to whatever action is proposed.

To host a constructive dialogue, make room for all interests and voices, Lewis advises. And, “Try to think more creatively about how to accommodate a value and to honor and protect other people’s fundamental interests.”

Calling All Citizens: Speak Up!

State Sen. Gail Schwartz has taken to the road. Schwartz represents District 5 on Colorado’s Western Slope and, through town hall meetings, is encouraging constituents to participate in creating Colorado’s Water Plan. “What I’m trying to stress to them is that you don’t have to have expertise in water to be part of the conversation and talk about your priorities,” Sen. Schwartz says. She invites people to speak up, whether by sending her an email, calling or attending a meeting.

The Gunnison Basin Roundtable, a state-designated group of leaders providing input into regional water planning, is also facilitating citizen involvement by publishing “A Handbook for Inhabitants.” This 32-page newsprint booklet, distributed widely through newspapers and by roundtable members, features topics such as where the basin’s water comes from and how it’s used, water quality, and the basin’s water future. It also encourages residents to connect with their water and participate in water planning by attending a roundtable meeting or offering feedback on Colorado’s Water Plan.

Meanwhile, agency representatives are using social media, connections with “touchstone” advocates such as reporters or active organizations within affected communities, and door-to-door outreach to seek input on permitting processes. Kara Lamb of the Bureau of Reclamation suggests visiting everything from personal residences to local homeowner association meetings and club gatherings to “fold them into the process.” Says Lamb, “I try to do that over and over, going to where the concerned voices are. It isn’t always easy and we’re not always welcomed, but I think we have to try.”

Print

Print