For the vast majority of Coloradans, water is as close as the nearest faucet. Clean, cheap and seemingly abundant, it flows at the turn of a knob. How, then, to persuade people that the substance is actually scarce and precious—needed not only for drinking and landscaping, but for sanitation, agriculture, natural resource extraction, manufacturing and, of course, for keeping rivers flowing?

Moreover, how to engage the public in activities such as protecting or restoring waterways or working toward solutions to possible water shortages? The answer: water education.

Since the first covered wagons creaked across the borders of what is now Colorado, water education has been ongoing, although in the earliest days it was as rudimentary as old-timers warning settlers, “Don’t build too close to that river,” or “It gets mighty dry here in July.”

Today, water education has burgeoned into a richly diverse field that seeks to inform citizens and leaders about everything from the need for conservation to the complexities of water law, from the basics of irrigation and Xeriscaping to the dangers of flooding. Across the state, a plethora of programs offer workshops, tours, trainings, festivals and seminars geared to audiences of all ages and levels of expertise. Water educators visit classrooms, host field trips, and disseminate information via every type of media available. Yet the job is far from finished, and some worry that all the efforts aren’t enough.

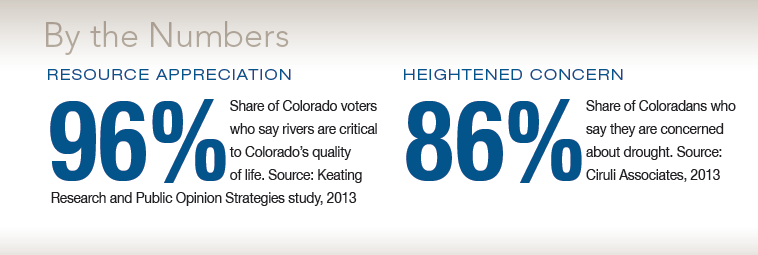

As Colorado grows, it not only faces the challenge of meeting water supply needs, but also of educating new residents unfamiliar with the state’s water issues. “This is a critical time to educate Coloradans on one of our most valuable resources,” says Alan Hamel, chair of the Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB), noting that the state is expected to fall short of meeting forecasted water demands within the next 40 years.

Judy Lopez, executive director of the Rio Grande Watershed Conservation and Education Initiative, agrees: “If we don’t start getting folks used to the idea that we can live with less, we’re setting ourselves up for some rude surprises.”

Educating Coloradans will be crucial not only so they can use water wisely but also so they can vote thoughtfully or participate in planning processes involving complicated issues such as transbasin water diversions, water transfers from agriculture to municipalities, or hydraulic fracturing. And it will be essential to educate current and future leaders so they can also make informed decisions and find creative solutions to challenges.

“It’s important for a person to know where to get sound water information that is not one-sided,” says Tom Cech, director of the One World One Water Center for Urban Water Education and Stewardship at Metropolitan State University in Denver.

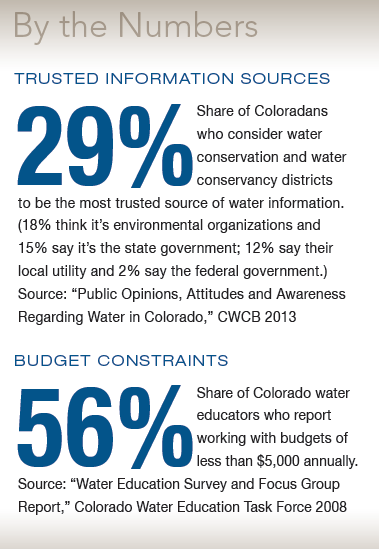

Fortunately, from nonprofits and academic institutions to state and federal agencies, water conservation and conservancy districts, public utilities, and private businesses, a wide range of entities are working to reach the public. In addition to education, many efforts seek to engage people through stakeholder groups or public comment opportunities on water-related proposals. But there’s still a knowledge and awareness gap ripe for water educators to fill.

Water Education Evolves

Organized water education in Colorado developed slowly. Among the earliest efforts was the Colorado Water Workshop at Western State Colorado University in Gunnison, started by water attorney Dick Bratton and history professor Duane Vandenbusche in 1976 to bring people together from both sides of the Continental Divide. Recognizing the inherent conflict in water issues, the founders offered one basic principle, recalls WSCU’s Environment and Sustainability Program director Jeff Sellen: “Let all reasonable positions be represented.” That same year, the Colorado Water Congress developed a teaching guide for each of the state’s watersheds geared to children. But these were isolated efforts.

“Back in the early ’80s, I don’t recall much of what we call water education occurring, other than bus tours and newsletters,” says Cech. A few municipal providers such as Denver Water and Aurora Water did offer educational programs for youth, he says.

Things began to change in the late ’80s. The Central Colorado Water Conservancy District (CCWCD) in Greeley took advantage of U.S. Environmental Protection Agency grant money to fund the development of a K-12 water curriculum. The Colorado Division of Wildlife, a major player early on, helped create a water curriculum called “Splatte!” that focused on the South Platte River, while a water quality specialist with the agency, Barb Horn, launched the now-widespread River Watch Program that took school kids to the Yampa River to sample water quality.

In 1990, the first water-related exhibit, “Colorado Water: Liquid Gold,” organized by numerous water utilities and districts, was presented at the Colorado State Fair. Around that time, Cech, then with the CCWCD, was visiting his parents in Nebraska when he read in the local newspaper about a children’s water festival in Grand Island. “I called them up and found out how they did it,” he recalls.

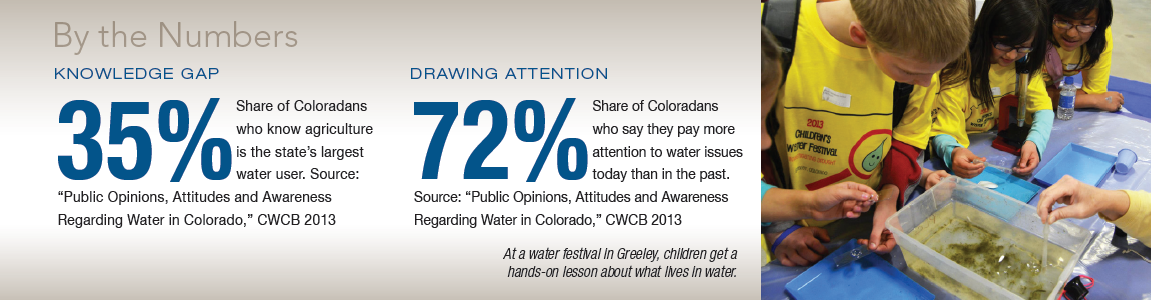

The result was Colorado’s first water festival in 1991. Presented by CCWCD, it drew more than 1,500 fourth- and fifth-graders. It was swiftly followed by others in Loveland, Fort Collins and Boulder. Today, there are festivals in dozens of locations statewide; the largest, put on by the Ute Water Conservancy District, brings more than 2,000 fifth-graders to the Colorado Mesa University campus in Grand Junction every year for a day of fun, hands-on learning activities.

Reaching adults was a whole other can of worms, difficult because of busy schedules and competing priorities for their time. As one of the state’s oldest water education organizations, the Water Information Program based in Durango has been tackling this problem since 1994, when the Animas-La Plata and the Dolores Water conservancy districts got it off the ground, with the Southwestern Water Conservation District as a participating entity. Among WIP’s early offerings were informational brochures, selected news clippings copied and sent by mail, and traveling displays.

Water Information Program coordinator Denise Rue-Pastin hopes that once people understand the value of water, and its relative scarcity, their awareness will result in calls to action or change. Photo By: Jeremy Wade Shockley

But although water education was spreading, there was little sense of urgency about it prior to the new millennium, Cech says. “From 1980 to 2000, Colorado was in one of the 20 wettest years in recorded history,” he says. “Some of us said, ‘You know, we need a drought to get people interested in water.’ I wish we hadn’t said that, because then the worst drought in 400 years occurred.”

Since that drought in 2002-03, people’s desire to learn about water has increased dramatically, Cech says. He recalls seeing a short article about water in the Greeley Tribune in the ’80s and cutting it out “because it was so unusual.” Today, articles and public information about water issues abound.

As it continued to spread, water education evolved in other ways. Early public educational efforts were primarily issue or project-driven, led by federal and state agencies, municipal water districts, and water conservancy or water conservation districts—all government entities. Today there are many civically driven efforts, from conservation-oriented watershed groups to the River Protection Workgroups of southwestern Colorado, which have convened stakeholders in five river basins for a multi-year, consensus-based process to recommend future management tools. The shift to more democratic, grassroots water planning puts a greater emphasis on citizen input, but requires that those citizens be informed. So while youth programs remain a strong focus of educational efforts, there’s a more recent push to target the adult audience.

The Rio Grande Watershed Conservation and Education Initiative’s Lopez agrees that reaching adults is critical but thinks it remains one of the weakest spots in water education. She believes more hands-on offerings— along the lines of those provided for kids—are needed.

“Everybody says, ‘We can do a flyer,’ because it’s easy, but a large percentage of people never pick it up or read it,” says Lopez. “We have to do things that are interactive.” Lopez offers an annual expo for small-acreage landowners along with frequent field trips for the public, including site visits to see new infrastructure. Such visits create a sense of familiarity and let people see how their money is invested, says Lopez.

Meanwhile, the Water Information Program has expanded to include 17 participating entities, offering everything from a lending library and website with up-to-date water news to teachers workshops and an annual one-day course, “Water 101,” that includes an overview of water law as well as topics relevant to each year’s hosting locale. The course, now in its eighth year, provides continuing education credits for realtors and attorneys, but about one-third of attendees are citizens who just want to know more, says Water Information Program coordinator Denise Rue-Pastin.

Meanwhile, the Water Information Program has expanded to include 17 participating entities, offering everything from a lending library and website with up-to-date water news to teachers workshops and an annual one-day course, “Water 101,” that includes an overview of water law as well as topics relevant to each year’s hosting locale. The course, now in its eighth year, provides continuing education credits for realtors and attorneys, but about one-third of attendees are citizens who just want to know more, says Water Information Program coordinator Denise Rue-Pastin.

One thing that has not changed over the decades is the importance of the central message about water’s scarcity and the need for conservation. “People tend to take it [water] for granted,” says Rue-Pastin. “We hope once they start to understand issues such as supply and demand, that will create some calls to action or change.”

While the core message may not have changed, Kathy Parker, public information and education officer with the CCWCD, says the message has shifted somewhat over the years. “It used to be more about the water cycle and conservation,” she explains. “Now the educators are starting to tackle tougher issues like sharing water and the lack of water.”

Dr. Reagan Waskom, director of the Colorado Water Institute, an affiliate of Colorado State University working to connect the expertise of higher education to the state’s water challenges, believes the messages have needed to change to keep pace as society, its water needs, and water management have changed. “For example, the recent focus on the non-consumptive needs of rivers and ecosystems received little discussion in earlier decades; now it is truly mainstream,” says Waskom. Or, he continues, “Whatever you think about the fracking issue, you can see many communities currently having in-depth dialogue about sophisticated aspects of drilling technology and climate change around this topic. Water educators have to stay on top of a lot of issues to remain relevant.”

Advances For A Broader Reach

Colorado’s General Assembly has repeatedly demonstrated the importance it places on water education. In 2000, it appropriated funds to develop a water education curriculum for K-12 students as well as adults, an effort that continues today with different funding sources. In 2002, state legislators created the Colorado Foundation for Water Education (CFWE)—a critical step, says Cech, because it represented “the first concerted effort by a nongovernmental entity to focus on the general public.”

Then in 2005, the Colorado Water for the 21st Century Act established a basin roundtable for each of Colorado’s eight river basins (plus the Denver metro area) as well as an Interbasin Compact Committee to facilitate statewide solutions. Among the duties of the roundtables is to serve as a forum for education and debate regarding methods for meeting water supply needs.

Educational efforts have intensified over the last decade or so, culminating in the statewide Water 2012 campaign, designed to raise public awareness of water and timed to coincide with the 75th anniversary of the creation of the Colorado Water Conservation Board, the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District and the Colorado River Water Conservation District in 2012. Led by CFWE, the campaign reached more than a half-million people.

But the CWCB’s Hamel believes some of the momentum of Water 2012 has been lost. And on a scale of one to 10, Cech rates the effectiveness of current water education in reaching the average citizen at a three. “There’s a lot of room to do more,” he says, adding that many people still do not understand where their water comes from or where it goes after they use it.

Like many endeavors, time and money are limiting factors in educational efforts. This was a key finding in a 2008 survey of 292 Colorado water education providers conducted by the Water Education Task Force of the CWCB. Many groups have found that working with partners can help stretch resources. For example, the West Greeley Conservation District, CCWCD, and city of Greeley’s water conservation and stormwater offices have combined forces to host joint water festivals and river cleanups. They also work together on Project WET (Water Education for Teachers) workshops, school presentations, and seminars to train people in the Community Collaborative Rain, Hail and Snow Network (CoCoRaHS), a nationwide network that enlists citizens in taking daily precipitation observations. “The partnership is growing and snowballing,” CCWCD’s Parker says. “It has exponentially multiplied what we’re able to do with our finances and manpower and resources.”

To assist other organizations in partnering, CFWE teamed up with the Colorado Alliance for Environmental Education to develop a web portal/repository of statewide resources called the Water Educator Network. The goal is to facilitate collaboration between groups with overlapping aims.

Another effort, spearheaded by Colorado WaterWise, is a “Value of Colorado’s Water” communications toolkit to provide effective educational materials that can be customized for specific audiences. WaterWise has issued a call for sponsors to contribute thefunds for hiring a professional marketing consultant to develop the toolkit, targeting December 2014 for its release.

Carbondale Middle School students take a walking field trip to investigate aquatic life in the Crystal River.

Youth water educators must also be increasingly creative to get into schools, where recent state emphasis on back-to-the-basics instruction has made it more challenging to win time with students. Birgit Landin, youth education consultant with Colorado Springs Utilities, who presents in classrooms across four school districts, says she and her co-workers continually adapt their curriculum to meet new academic standards. “The whole educational front has changed dramatically,” says Landin. “What teachers are required to do is so different from 10 years ago. Teachers have to be able to show that our program will meet the standards of the core curriculum before they can give us permission to come to their classroom.”

Water educators continue to strategize and identify new ways to reach audiences— and there is no shortage of work to be done. “There’s a youth audience that is changing every year. We’re never done with youth education,” says Waskom. The challenge is to capture the interest of kids absorbed in Facebook, smart phones and computer games. “They understand the hydrologic cycle, but they say, ‘So what?’ We found in focus groups that the dry science or the policy of water isn’t very compelling to kids. You need to get them outdoors, into the watershed, and tie education to recreation and things they care about.”

Waskom says there is also a continuing need for adult education because of the state’s changing demographics. “People who have been here very long—I think they’re pretty aware. But you have people moving here from back East. Water education is one of those things we’ll never be finished with.”

Cech believes water education is “leaps and bounds” ahead of where it was 20 or 30 years ago. “In some ways we’ve done a wonderful job with water education. But I think it’s still the tip of the iceberg. We always need to reach more people.”

Print

Print