The world of water management is complex, and because everyone has a stake in the resource, decision-making processes can be technical and cumbersome. But that doesn’t mean citizens shouldn’t speak up about issues that matter to them. With federal and state laws mandating public comment processes, agencies and legislators looking to hear from their constituents to develop solutions to water issues, and advocacy organizations rallying citizens to make their voices heard, the challenge is knowing where to begin.

If an irrigation company or utility hopes to build a dam, for example, they might deal with myriad government agencies and go through a separate public comment process for each. For those interested in participating, the challenges of reading long documents, submitting comments through official feedback mechanisms, tracking agency responses and remaining engaged for what could be years to see evidence of change can be prohibitive.

When a project with a federal nexus evolves, agencies must legally disclose information about that project. Depending on the proposal, they may be required to provide outlets for engagement under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), soliciting public feedback related to the environmental impacts of the project and considering all comments received on a draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) before it is finalized and distributed. Similar processes exist at the state level. Entities putting forth water projects must craft a fisheries and wildlife mitigation plan with Colorado Parks and Wildlife staff. These plans integrate comments received on related EIS’s and garner additional feedback of their own.

Permitting can be long, arduous and frustrating for everyone involved. In the case of the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District’s Northern Integrated Supply Project (NISP), the process has continued for a decade. To date, Northern has spent between $10 and $12 million on behalf of NISP’s project participants, and much more remains to be done. At the same time, citizens have followed every step due to concerns about the project’s impacts. Still, such processes aren’t there just to be difficult, says Becky Long, advocacy director with the nonprofit Conservation Colorado. Instead, they’re in place to help leaders answer key questions and choose the best path forward.

That feedback process is crucial, agrees Kara Lamb, public involvement specialist at the Bureau of Reclamation, and it makes a difference. For example, when Reclamation modernized the dams at Horsetooth Reservoir 13 years ago, staff didn’t realize the importance of rock climbing around the reservoir until climbers spoke up. The climbers’ input enabled the agency to preserve most access points. “We wouldn’t have had that information if they didn’t come forward, so [NEPA] does work,” says Lamb.

Significant roadblocks, however, according to Long, are that people aren’t always sure how to engage and then when they do, they can leave wondering whether their comments entered a vacuum. “It makes them feel like, ‘Why should I [participate], because last time it went into a big void,’” Long says.

Lamb sees the same problem, but traces it back to a common misconception: People want to “vote” through NEPA, assuming that if enough of them express their dislike for a project, the agency will shut it down, Lamb says. The NEPA engagement process doesn’t account for personal opinions, and in most cases, won’t result in a project’s demise; rather, it exists to collect, disclose and analyze information. “People say, ‘If I stood up, why isn’t my voice being heard?’” explains Lamb. “But what NEPA is looking for is tangible and scientific.”

A famous example of the process at work, and one that still echoes in Colorado, is that of Two Forks, the 1 million-acre-foot reservoir put forth by Denver Water in the 1970s and ‘80s that was denied a Clean Water Act 404 permit to “dredge and fill” by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Although the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was prepared to issue that permit, the EPA disagreed, finding that the project would cause serious environmental damage, avoidable with an alternative plan—an alternative that existed thanks to public involvement.

Dan Luecke, regional director of the Environmental Defense Fund at the time, put together the alternative that the EPA used to deny the Two Forks permit. Like Lamb, Luecke highlights the importance of that tangible, scientific information in influencing decision-making. “The public can get involved in these processes to make their opinions known and they very much did in Two Forks,” he says. “But those who would oppose a certain project or advocate for an alternative have got to have significant technical capabilities to accomplish much.”

“I don’t know that there is any easy solution,” adds Luecke. “But that doesn’t mean the public shouldn’t get involved; that doesn’t mean the public shouldn’t stand up.”

The Role of Advocacy Work

“In the world of changing the world, decision-makers hold all the power,” says Joshua Ruschhaupt, director of the Sierra Club’s Rocky Mountain Chapter. “The question is who can influence those decision-makers and how.”

Decision-makers include anyone in a position of authority when it comes to making choices or creating policy. Advocacy groups like the Sierra Club and Conservation Colorado employ a suite of tactics to influence decisions, some which engage the general public and others that rely on professional staff. “We do the best we can so that we’re at least holding our own and bringing good science to the table for those decision-makers to understand before they make a decision,” Ruschhaupt says.

Generating public activism could mean providing a link on email blasts for subscribers to send comments to government officials, organizing people to testify during hearings at the capitol, or recruiting volunteers to help inform others.

Sierra Club members speak out on climate change.

Conservation Colorado determines which actions make sense on an issue-by-issue basis, says Becky Long, the group’s advocacy director. While engaging Coloradans around a recent resource management plan in Grand Junction, for example, Conservation Colorado led tours and hikes to get people on the ground, where they could see what’s happening. Tours and actual experiences help people provide substantive comments and care more about the topic. Says Long, “The heart of advocacy work is demonstrating to people why it matters.”

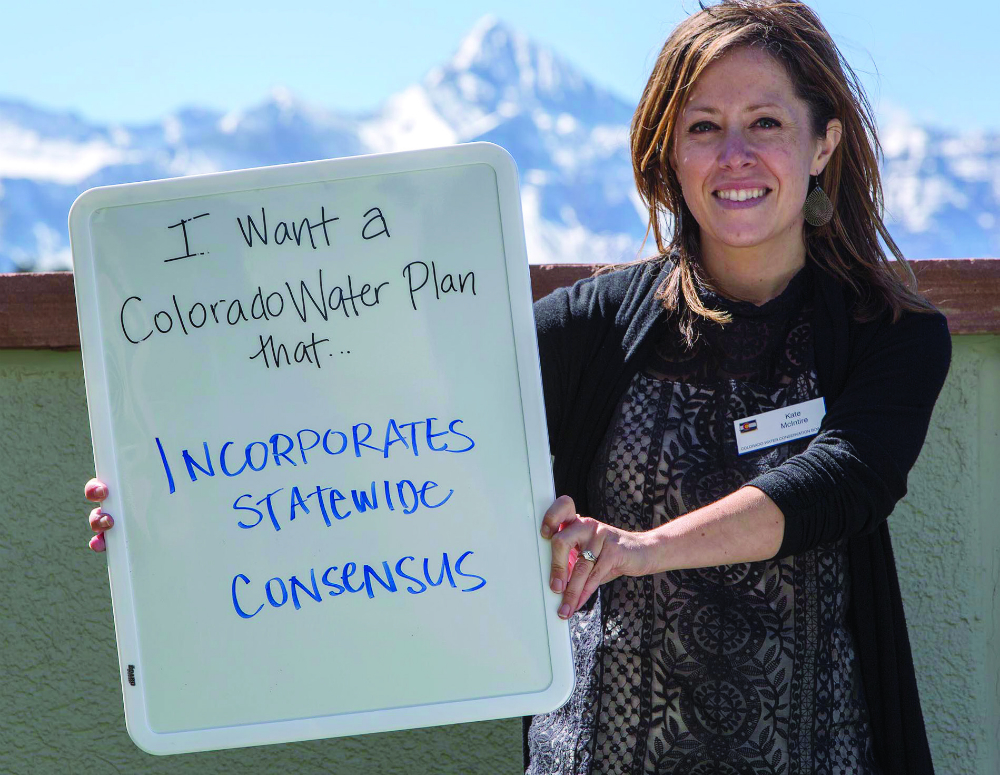

Kate McIntire of the Colorado Water Conservation Board is leading outreach efforts to involve Coloradans statewide in Colorado’s Water Plan.

Print

Print