Colorado boasts above-ground reservoirs and below-ground aquifer storage; reservoirs that are owned and managed by a single entity and others that are shared; storage that meets the needs of municipalities, farmers, the environment and recreation. It also has dams that serve as flood control and others that hold back water to release later to downstream states. There is storage to enable water reuse and recycling; storage that facilitates water sharing; storage as an important logistic in water treatment; and storage as a waiting place before or after water is used to generate hydropower. There are reservoirs to hold more than 940,000 acre-feet and others that hold less than 1 acre-foot. There are natural lakes used to store water, and an order of magnitude more manmade reservoirs.

The flavors of storage are as diverse as the terrain and regions of the state, and that storage allows for our way of life. In planning to meet the needs of the future, water storage will undoubtedly remain a crucial piece of the water supply and management picture, as it has for centuries in Colorado and elsewhere around the West. Yet, given the time and expense as well as environmental impacts associated with the construction of dams and reservoirs historically, the pursuit of storage alongside other water supply-and-demand-balancing strategies, such as water conservation, reuse and water sharing, is being prioritized by the state through the multi-faceted state water plan.

As one of eight measurable objectives, the 2015 Colorado Water Plan set a goal of attaining 400,000 acre-feet of additional water storage by 2050 to better manage and share water. An updated plan is expected by 2022 when that goal will likely be revisited and adjusted to account for reservoir projects that have since been completed.

Only five years after the plan was set in motion, Colorado isn’t far from meeting that goal, although some of the big projects that are already built or permitted were in the works a decade or more before the plan included them. According to the Colorado Department of Natural Resources, 20,600 acre-feet of new water storage has come online since 2015 through the southwest metro area’s Chatfield Reallocation Project. Another 454,500 acre-feet of additional storage is either permitted or in permitting through Southern Delivery System components Bostrom Reservoir and Williams Creek Reservoir, Northern Water’s Northern Integrated Supply Project, the Northern Water Municipal Subdistrict’s Windy Gap Firming Project, Denver Water’s Gross Reservoir Expansion, the City of Fort Collins’ Halligan Water Supply Project, and the Ute Water Conservancy District’s Monument Reservoir Enlargement Project.

If all of that is eventually approved and constructed, it will total more than 400,000 acre-feet. Such storage volume hasn’t come online in Colorado since the 1980s. Even with the goal in sight, water providers and others continue to pursue storage to maximize the use of Colorado’s water and shore up against drought. Those most likely to be successful are those with innovative plans — collaborative and low-impact projects built with the environment in mind.

Into the Modern Storage Era

Most Coloradans rely on some form of water storage in order to live. Water is collected when available and later released when and where it’s needed. Water storage is a necessity, providing year-round access to water that would otherwise come in a rush each spring as snow melts into runoff and flows hurriedly out of state.

“If we were to leave it up to the natural systems, we would be dry for a big part of the year,” says Lauren Ris, deputy director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board. (Ris also serves on the Water Education Colorado Board of Trustees.)

The Ancestral Puebloans, who once inhabited the Four Corners region, knew this and relied on water storage like Morefield Reservoir, which anthropologists indicate was used between 750-1100 A.D. and is still evidenced by mounds in Mesa Verde National Park.

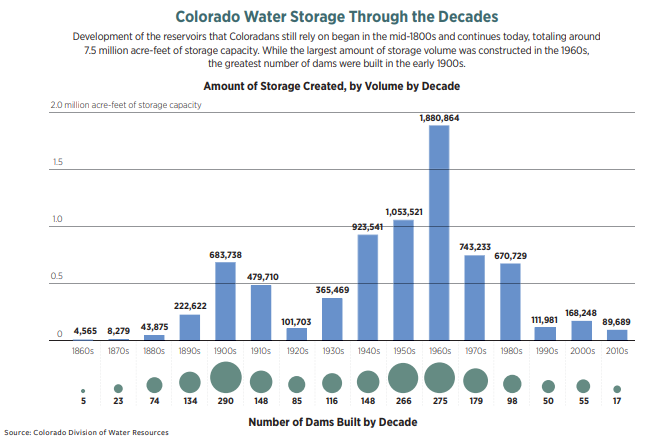

Years later, upon settlement by non-native populations including land grant recipients, homesteaders and miners, reservoir construction proved vital to sustain a larger population. Dams were rapidly constructed in the late 1800s through 1910, primarily for agricultural water needs. In the early 1900s some 290 dams were built in Colorado, the most dams erected in a single decade.

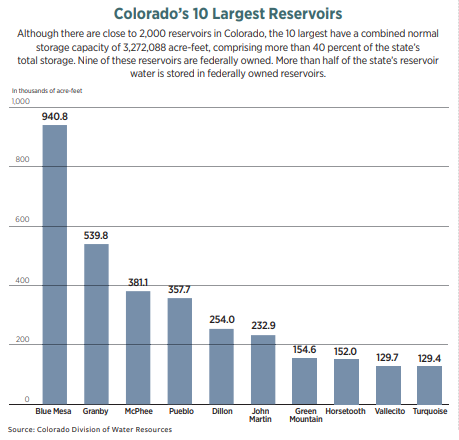

The 1930s through 1970s brought a boom of reservoir construction to meet the demands of the state’s growing municipal water needs. Toward the end of this municipal era, the 1960s saw the greatest water storage volume constructed in any decade, with more than 1.8 million acre-feet, including two of the state’s largest water bodies: Blue Mesa Reservoir near Gunnison and Denver Water’s Dillon Reservoir.

The rapid construction of big storage projects in Colorado and the West slowed starting in the 1970s as environmental laws and community concern about environmental impacts grew stronger and project permits became more difficult to obtain. The 1980s Two Forks dam and reservoir project debate and subsequent veto, where local community groups raised enough opposition to stop a planned 615-foot dam southwest of Denver, was a turning point. Two Forks marked the very end of the era in which big reservoirs were the primary answer to Colorado’s water supply, and the start to substantial community involvement.

The past 10 years have brought the fewest new dams and least amount of new storage volume in 120 years. Yet the call for storage from stakeholders across the state continues. Through the 2015 statewide water planning process, basin roundtables — stakeholder groups who have been working together on a regional, river-basin-wide scale to develop water priorities, assessments and goals — developed Basin Implementation Plans. All of the eight plans identified the need for new, restored or better-maintained storage.

As the roundtables update their Basin Implementation Plans this year, many continue to focus on storage as an important strategy to use alongside others to meet future water demands. The South Platte Basin, which faces the largest projected shortfall in water available for municipal and industrial uses of any basin in the state, with a projected maximum annual gap of up to 540,700 acre-feet per year, is among them. Additional storage could help meet part of that projected gap, including projects that are working through the permitting process from Northern Water, Denver Water, the City of Fort Collins, and others.

“Storage is going to remain a focus moving forward,” says Garrett Varra, chair of the South Platte Basin Roundtable. “It’s getting more specific, more dialed in, with more interest from more and more parties and the benefits [of new storage] just keep multiplying.”

Environmental Costs

While undeniably beneficial to Colorado water users, storage projects, even those designed to incur low impacts, alter the environment by interrupting natural hydrology.

“When you change the hydrology, you change the water, you change everything,” says Julie Ash, a senior restoration engineer at Stillwater Sciences. Ash explains that when a dam is built, it alters the amount, peak, duration and timing of flows, which in turn changes the way sediment moves in the stream channel, which then changes the shape of the channel and affects the habitat available to fish and wildlife. Changes in hydrology also affect the species of fish that thrive in Colorado’s rivers, a fish’s ability to reproduce, water temperature, and the migration patterns of birds, which are tuned to peak runoff and base flows.

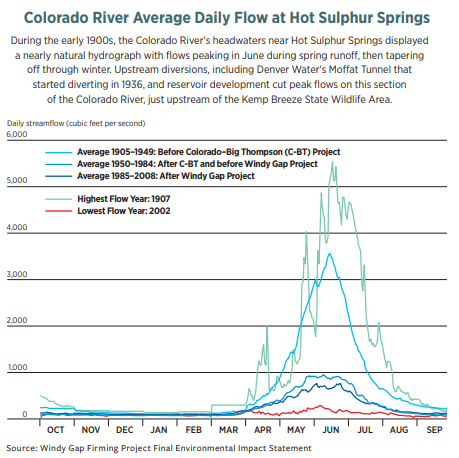

A natural flow pattern on an undammed, undiverted river in Colorado reveals a high peak every spring. Then, as snow disappears, streamflows drop to “base flow” levels, the lowest sustained flow level.

“Everything evolved to that [natural] flow regime,” says Johannes Beeby, Ash’s colleague, a hydrologist at Stillwater Sciences.

The effects of on-channel reservoir storage are widely publicized but tiny diversions, too, can cause an additive impact. Take, for example, the Poudre River, home to numerous diversions of all sizes.

“It’s super fragmented. It’s about the river being chopped up lots of times,” says Jennifer Shanahan, a watershed planner for the City of Fort Collins’ Natural Areas Program. Whether it’s a large diversion or many small ones, “it’s the same thing — they take water off and cut sediment flows,” she says. The diversions cause blockage to aquatic communities, fisheries, water flows and sediment, pulling water off of the river and away to small reservoirs dotted across northeastern Colorado. “We’ve seen over time the decrease in the native diversity of fish in our river,” Shanahan says.

But recognizing these impacts creates an opening for improvement. The City of Fort Collins, after Shanahan’s department led the way on a river health assessment, is working on floodplain restoration along the Poudre River. Plus, new water storage projects including the Northern Integrated Supply Project and Halligan Water Supply Project are partners on the Poudre Flows Project and are including some water for instream flows into their operations to keep water in the Poudre River. “We have a huge legacy but we also have an opportunity,” Shanahan says.

Mitigation and Enhancement

Extensive federal, state and local permitting processes are in place to minimize and mitigate, or directly offset, the impact of water storage projects. Mitigation is typically required in permitting to offset impact, so, for example, if a new storage project is going to fill in an acre of wetlands, an acre of wetlands work will be substituted elsewhere.

Approval to construct a storage project can take decades but the aim of permitting is to strike a balance: to protect the state’s natural resources and give the public a voice, while also providing a path for water providers and others to pursue the projects needed to support Coloradans. For project proponents, mitigation work can be prohibitively time consuming and expensive, and yet, mitigation doesn’t always go far enough. That’s where “enhancement” projects come in. These are efforts by project proponents that go beyond the required mitigation of expected project impacts to actually improve and repair existing stream conditions.

Beeby, Ash and the Stillwater team are working with Denver Water, Northern Water and Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) on an enhancement project at the Kemp Breeze State Wildlife Area, which sits alongside the Colorado River in Grand County. It’s downstream of the West Slope Colorado-Big Thompson (C-BT) Project reservoirs and Denver Water’s Williams Fork Reservoir. By the time the Colorado River reaches Kemp Breeze, about 60% of natural flows have been diverted, stored and transported across the Continental Divide to the Front Range. Here, in addition to depleted flows, dams have significantly altered the historical hydrology and impacted riffles, leading to a decline in populations of giant stonefly, sculpin and trout.

“[This stretch of the Colorado River] has been frozen in time since like the 1930s,” says Beeby — construction began on the cluster of nearby dams and transbasin diversions in the late ‘30s. Comparing a photograph today to a photo of the river taken in 1938, the width, depth and shape haven’t naturally meandered or changed — it’s identical, he says, because of the managed flow regime. Its level of ecological function is similar to that of a concrete canal.

Through Denver Water’s proposed Gross Reservoir Expansion Project and Northern Water’s Windy Gap Firming Project, the water providers created Fish and Wildlife Enhancement Plans and signed an intergovernmental agreement with CPW to restore a 16.7-mile stretch of river between Windy Gap Reservoir and Kemp Breeze. If their storage projects are approved, Northern Water’s Municipal Subdistrict will contribute $4 million and Denver Water will contribute $2 million to this restoration site. Some additional funds will come from CPW and Learning By Doing.

The plan at Kemp Breeze is to fix base processes so the river can restore itself, stretching the impact of the investment in the river because, while $7 million sounds like a lot of money, it won’t touch the full 16.7-mile stretch of river. To fix those processes, Stillwater plans to do gravel augmentation (dumping sediment below the dam), narrow the channel, and install wood structures that will restore sediment transport processes. Denver Water and Northern Water will also avoid capturing peak flows for three days each year, allowing natural hydrology to do its job by flushing the river and moving sediment. Eventually, CPW will monitor the project and, through Learning By Doing, try a different tact if the stream isn’t functioning as planned.

Mitigation is always a negotiated compromise, says Ken Kehmeier, a former senior aquatic biologist and mitigation specialist with CPW, now retired. Mitigation overseen by CPW during the permitting process is guided by statute that directs the agency to find a balance between the needs of fish and wildlife resources and the need to develop. It takes a lot of conversation and foresight to develop a project while minimizing and mitigating impacts, he says. And, while mitigation is important, so is the careful consideration of which projects are built.

“When new reservoir construction happens, it will change the landscape forever,” Kehmeier says. “The need for reservoir storage is a reality, but so are the associated impacts to natural resources and people. So there needs to be a very deliberate choice, a conscientious choice about what we’re doing, why we’re doing it. Then, how do we protect or enhance the environment to the greatest extent possible?”

Building Smarter Storage

Time will bring more challenges and successes as storage is built and mitigation – and sometimes enhancement – is implemented. “It’s not about if [reservoirs] get built, it’s how they get built,” says Russ Sands, chief of the Colorado Water Conservation Board’s Water Supply Section. Sands sees his agency’s role as one that convenes and advances conversations so that new water storage is built in smart, multi-purpose ways. “How do we advance storage in a way that minimizes impact and maximizes benefits?” he asks.

The state is incentivizing, and projects are being planned, with built-in environmental benefits, such as Fort Collins’ Halligan Water Supply Project, which will rehabilitate and raise an existing dam, then use some of the reservoir’s expanded capacity to release year-round minimum flows to prevent stream dry-up. Others are being devised as system-wide collaborative projects, like the South Platte Regional Opportunities Water Group (SPROWG), where a series of reservoirs, pipelines, and complex water rights exchanges between water users throughout the South Platte Basin could significantly lessen the need for any single, large and likely more environmentally damaging project. Then there are projects that focus on taking advantage of natural infrastructure, such as underground aquifer storage and recovery, or even work to improve soil health and forest health, boosting the landscape’s capacity to retain water.

With all of these projects, water storage isn’t the only answer to Colorado’s water supply challenges. “Cities and water users have several options to find water,” says Varra.

Capturing excess flows during peak runoff with these storage buckets is just one of them, though some degree of storage enables other water supply solutions too. Water reuse projects often rely on some amount of storage as water cycles through treatment systems. Alternatives to agricultural water transfers, which help avoid buy and dry through water sharing agreements, typically rely on the flexibility to divert and re-time water that is enabled by storage. It’s all part of the water supply puzzle. “To be successful, we have to be successful in all of these things,” Sands says.

Print

Print