Last week, June 2 and June 4, the Colorado Foundation for Water Education led its annual Urban Waters Bike Tours along the South Platte River, starting at Chatfield Reservoir. Journalist Bob Berwyn joined one ride and combined that experience with his own exploration of the South Platte. Read his full article here. Berwyn writes:

Sometime soon, the [Chatfield] reservoir will also be supplying water to growth areas like Centennial under a 2014 deal that changes the way Chatfield is operated. Those changes have spurred concerns about flooding along the shore of Chatfield Reservoir, State Senator Irene Aquilar (D-SD32) said during a recent urban-water bike tour offered by the Colorado Foundation for Water Education.

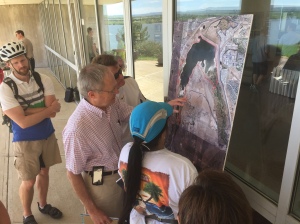

During the introduction to the tour at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Chatfield visitor center, state park manager Scott Roush acknowledged that parts of the shoreline will be permanently flooded. Hundreds of cottonwood trees will die, but new groves will spring up at a higher level along the shore.

The jostling over huge amounts of water is typical along the Front Range. There are 20,000 acre-feet at stake in Chatfield Reservoir, enough to fuel a local real-estate boom, which, truth be told, is already under way, and not everyone is convinced that places like Centennial have their water figured out.

But the urban-waters bike tour isn’t about politics — it’s about learning how people live with the South Platte, from the new residential neighborhoods in the dry hills around Chatfield on down to the industrial, urban heartland of southwest and south-central Denver. How do you manage something that is a potential threat, and at the same time, a precious resource?

With the introductory speeches done, a couple dozen cyclists from around the Metro area don helmets, fill their water bottles and saddle up for the ride along the storied river.

Rolling past the reservoir’s factory-size outlet-works, where the river pours into the cobbled plain below, Aguilar says it’s good for citizens, and lawmakers, to see these water-works first-hand. A new state water plan will go to the Legislature at the end of the year, and there may be some tough budget decisions ahead.

Parks

“It’s nothing like 1965,” said South Platte Park supervisor Skot Latona, pointing at the metal flood sculpture that commemorates the the high-water mark of the historic flood. But this year, the river has also delivered quite a punch, flowing at a near-record level.

Today, there is so much water in the channel that Latona can’t show the group a new set of riverside viewing and fishing decks. “They’re underwater,” he said wryly, explaining how the community responded to the 1965 flood.

Instead of digging a super-deep channel to trap the river during high flows, Littleton helped pioneer the concept of restoring a floodplain that allows the river to spread out naturally, as much as possible in an urban environment, Latona explains.

But the modern era of river management has brought other problems. At times, the river’s natural flow in Littleton is so low that treated effluence from wastewater plants makes up the vast majority of the flow farther downstream. The natural flow can go as low as half a cubic foot per second (about 3.5 gallons), while the treated wastewater volume is 7 or 8 cubic feet per second (about 52 gallons).

Latona’s handout for the tour includes a litany of common urban river problems, from invasive plants and litter to urban pollution. But the brochure makes it clear that Littleton doesn’t yet know exactly how the changes in Chatfield Reservoir will affect the park, one of the kinds of questions a coordinated state water plan could help answer.

The South Platte here in Littleton is one of the most-tested stretches of river in the state. Konowal says scientists search for bugs, algae and chemicals, and also measure temperatures. Based on those readings, the health department determines if the river is meeting environmental targets.

Those standards are high for the South Platte, which is used for drinking water, recreation and crop watering, and also provides habitat for some threatened fish species.

In a methodical, science-based process, the water experts create detailed maps showing exactly which South Platte tributaries may be close to the threshold for potentially dangerous E. coli bacteria or where the water is becoming too warm for fish and bugs. If the thresholds are crossed, the state must, under the Clean Water Act, develop a cleanup plan.

Previous cleanup projects have resulted in a reduction of toxic heavy-metal contamination in the South Platte. Periodic five-year reviews by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment ensure that the state stays up-to-date with federal environmental standards.

The urban zone

From South Platte Park, the bike path runs alongside the river and right into south Denver’s urban sprawl. At the C-470 underpass the water laps at the edge of the trail, with tangled willow shrubs sprouting in the cool shadow of massive concrete abutments.

Everything that happens along a river’s course – from high alpine headwaters through the cities and fields downstream – is connected, says scientist Scott Griebling, who studies endangered bird species in Nebraska that depend on South Platte water.

The closely watched birds need certain river conditions to thrive. But the way the river is used in Colorado doesn’t provide those flows, so huge swaths of cottonwood trees are taking over the birds’ habitat.

As scientific understanding evolves, most ecologists say that water managers need to think about river environments in bigger terms– including everything from the high mountain headwaters down to the river mouths – as they decide how to divide the flows.

Flush hard

Dennis Stowe, manager of the Littleton/Englewood Wastewater Treatment Plant, may not be thinking about the piping plover when he begins his presentation, but his urban neighbors in Thornton come to mind.

“Flush twice. Thornton really needs the water,” Stowe says, using a tired old water joke to illustrate the close connection between what comes out urban sewage systems and back into the South Platte River. Of course he offers the paper cup challenge beloved by water treatment operators. In one hand, he has tap water, in the other, the outflow from the plant.

Nobody takes him up on the taste test, but the point is made. By the time it runs through the system at the rate of 23 million gallons of water per day, it’s clean as can be — it has to be — because just a little farther downstream, boaters play in the water, fishermen cast for bass and other communities tap the river for their needs.

Water plan

A state water plan could help even at this nitty-gritty level by ensuring that people all along the state’s rivers understand the connections between what happens upstream to what happens ustownstream. For example, destroying wetlands in the high mountain valleys changes how fast and how much water flows downstream.

The water plan can also create more awareness about how climate change could disrupt the delicate cycles of precipitation and temperatures that govern flows, and it could spell out a plan for making flood control and water treatment systems more resilient to changes.

A recent state-sponsored study singled out the state’s water supplies as being especially vulnerable to disruptions. Some climate projections suggest there will be an increase in extreme weather, including big rainstorms. If those storms were to coincide with warmer spring temperatures and rapidly melting snow, it could lead to record-setting extreme flooding, which would put all those carefully planned water systems to a big test.

Gain your own first-hand experiences to learn about Colorado water. Save the date to join the Colorado Foundation for Water Education’s upcoming Vine to Wine tour in the Grand Valley July 24.

Print

Print

Reblogged this on Coyote Gulch.