The cost of everything has increased- movie tickets, food, and of course water rates– making the cost of water a source of contention from time to time. Still, people don’t always realize how much is factored into water rates. From the Winter 2013 issue of Headwaters magazine, Chris Woodka writes about the Art and Science of Pricing Water:

The cost of everything has increased- movie tickets, food, and of course water rates– making the cost of water a source of contention from time to time. Still, people don’t always realize how much is factored into water rates. From the Winter 2013 issue of Headwaters magazine, Chris Woodka writes about the Art and Science of Pricing Water:

Today, both the treatment of Colorado’s water and the price structure are far more sophisticated. Just as there is a science to treating water to meet standards for health and safety, the pricing of water is closely studied.

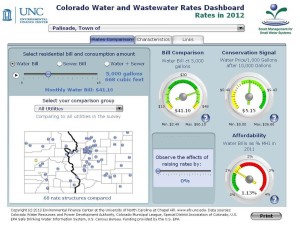

That’s why the Environmental Finance Center at the University of North Carolina developed the Colorado Dashboard, an online interactive tool that helps municipal and special district water and wastewater utility operators as well as policymakers, researchers, citizens and others find the information they factor into rate setting. Users can virtually adjust water rates and see how that impacts water bills, conservation and affordability. It’s interesting– give it a try.

This new dashboard uses data from a survey conducted by the Colorado Municipal League and Special District Association of Colorado and represents 112 municipal and special district drinking water and/or wastewater utilities in Colorado so users can easily look into:

- Bill Comparisons: How does the chosen bill compare to others in the selected comparison group?

- Conservation Signals: How strong or weak a price signal is being sent to residential customers at higher ranges of use (the price increase from 10,000 to 11,000 gallons per month)?

- Affordability: For a chosen residential bill, what percentage of median household income (MHI) does it represent? (See more on the MHI indicator in this recent blog post.)

Interested? Check out this blog post and Learn more about the Colorado dashboard and financial sustainability metrics for water systems through the Environmental Finance Center’s free webinar on August 30 from 12-1 pm. Click here to learn more about the training and to Register now!

Woodka explored some of those differences between utilities’ rates in his Headwaters article:

Every system is unique, and every utility has some sort of rate structure that takes into account the cost to buy water, treat it, pump it and maintain the infrastructure that delivers potable water to consumers’ taps…

The American Water Works Association provides guidelines for utilities in setting water rates, but more depends on the boards that govern cities, utilities or water districts and the nature of water systems. A developed water system with few capital costs likely will be able to keep its rates on a steady plane, while growing communities have to develop strategies that avoid rate shock while paying the bills.

Costs for water might depend on source of supply and whether the water comes from a system owned and maintained by the utility or purchased from another provider. If new, permanent water supplies must be acquired, the relative seniority and resulting dependability of the water rights also affects cost. In addition, some special districts rely more heavily on property taxes, particularly for capital improvements, which can offset the need for higher customer charges. But this diminishes flexibility—certain constitutional limits apply to property taxes but not service fees. Water bills may also include sewer and stormwater charges.

Beyond those factors, a growing community might require new users to foot the bills. “In simple terms, you’ve built it before they come,” says Rick Giardina of Red Oak Consulting, which assists hundreds of wa-ter utilities across the country with setting rates and other operational issues. Utilities build the cost of new service into one-time, up-front tap fees—virtually invisible charges included in the price of a new home or business. If those fees are set too low, existing customers could wind up footing a larger bill than necessary.

Social considerations also come into play when structuring rates. Some utilities might subsidize a minimum level of consumption to keep the price affordable for those least able to pay. Such an “essential use allowance” is typically based on the amount of water an average household would use for indoor use only. Similarly, a utility could delegate a portion of its revenue toward a payment assistance program.

A community might also use rates to attract large commercial users, charging them lower rates while asking residential customers to make up the difference; the benefit could be realized through economic development and an increase in the local tax base.

The rate structure could also be used to promote other social goals such as lowimpact development or green infrastructure that conserves water, says Giardina. “In the work we do, the first question we’re asked is ‘How do we compare with others?’ But without peeling back the layers of the onion, there are so many variables.”

Related articles

- The cost of water (yourwatercolorado.org)

- The Good News and Bad News of Declining Water Demand (newswatch.nationalgeographic.com)

Print

Print

Reblogged this on Coyote Gulch.