Cutting through red tape: Are new efficiencies in the state and federal permitting processes for large water projects changing our government for the better?

It’s been 16 years in the making. The Gross Reservoir Expansion Project, which aims to divert more water from the Colorado River for use by Denver residents, obtained most permissions to start construction in 2017. Yet, in 2019, it’s still waiting on one last federal permit (an amendment to Denver Water’s existing hydropower license from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission) and is working through local permitting with Boulder County.

Permitting water supply projects helps protect natural and cultural resources and communities and creates a venue for public comment and engagement around projects like dams and reservoirs which, if not mitigated, can have a major impact. While permitting itself is crucial, the process through which it’s achieved, more often than not, is repetitive, time consuming and costly.

Different projects require different permits, but many large water projects with a federal nexus must undergo environmental review under the National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA, to, in many cases, produce an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), a document that typically runs thousands of pages and takes the better part of a decade to complete. EIS documents include field studies, alternatives analysis, and public comment periods to provide a basis for both the public’s review of projects and a federal agency’s ultimate decision on whether to issue permits. In addition, many projects must also receive a biological opinion from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on impacts to endangered species and a 404 permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers under the Clean Water Act, which means a 401 certification from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) is also necessary. Project proponents often also develop a state-level fish and wildlife mitigation plan with Colorado Parks and Wildlife and the Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB). And, that’s not even an exhaustive list of requirements—many proponents must apply for other federal, state and local permits.

In 2015, the Colorado Water Plan identified permitting reform as a state priority, calling on state employees to take a look at shortening permitting timelines without reducing their environmental analyses’ scientific soundness and credibility. In the plan, the CWCB acknowledges the permitting process is “extremely difficult due to the complexity of the projects, the challenges in understanding and reducing environmental impacts, and the condition of many of the aquatic systems.” Yet water supply projects, coupled with other actions and strategies, are necessary to ensure there’s enough water for decades to come.

At the federal level, the One Federal Decision policy implemented via executive order by the Trump administration in August 2017 calls for permitting reform by requiring federal agencies to process environmental reviews as a unit: That means that all federal agencies involved in permitting a project will work under one schedule and will sign a single record of decision, rather than doing so individually by agency. The rule sets the goal of reducing the average time of processing such reviews and decisions at the federal level to a maximum of two years—a much shorter timeline than the Gross Reservoir Expansion’s 16-year effort.

A more abbreviated permitting timeline may open opportunities for smarter collaboration and more efficient work, but it also has the potential to place undue burden on water providers to get their analyses done quickly; in so doing, it may demand more staffing and money up front than some entities can afford. While water permitting experts have impressions of what the new policies and rules will do for the permitting world, it is too soon to tell whether this new guidance will make a substantive difference in the world of water project permitting, for better or for worse.

State-initiated processes

Eleven years elapsed between the kick-off of Gross’s EIS process in 2003 to the publication of a final EIS in 2014. It then took another three years before the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers issued its Record of Decision that allowed the project to proceed. After the draft EIS was completed in 2009, Denver Water worked on the Colorado River Cooperative Agreement, which took four years of mediated negotiations with water districts and cities on the Western Slope. At the same time, Denver Water joined forces with Northern Water and the Northern Water Municipal Subdistrict (responsible for the Windy Gap Firming Project) to develop a voluntary Fish and Wildlife Enhancement Plan to address impacts of ongoing operations on local species.

From Denver Water’s perspective, there was a lack of coordination on all those review processes. “We were rehashing the same issues; the same resources were getting reevaluated by each independent process,” says Paula Daukas, manager of environmental planning for Denver Water. She says recent efforts at the state level to identify “pain points” in the permitting process and to develop better ways to communicate and coordinate between project proponents, permitting authorities and stakeholders will help future projects avoid suffering some of the same inefficiencies.

If all of the state and federal agencies were able to come together and coordinate their permitting processes from the beginning, projects would be much more efficient, Daukas says. “There’s a benefit to trying to streamline the communication as much as possible,” Daukas says. “It should, ideally, knock years off the process.”

In response to the recommendations in the water plan, state officials and representatives of EPA Region 8 convened a meeting in 2016 with the goal of identifying ways to make the water supply permitting process “leaner,” or more efficient.

“Lean” refers to a discussion facilitation method participants used to identify places to trim fat. Colorado’s lean meeting allowed representatives from state, local and federal agencies, water utilities, environmental groups, and other stakeholders to share their experiences with large water supply project planning and permitting in Colorado and to weigh in on potential improvements to the process. One of the group’s primary findings was that better up-front coordination between local, state and federal agencies has great potential to create efficiencies in the permitting process, says Amy Moyer, the Colorado Department of Natural Resources’ assistant director for water (and a member of the Water Education Colorado Board of Trustees), who participated in the meeting.

Colorado Parks and Wildlife employees Katie Birch, instream flow coordinator, and Jeff Spohn, northeast region senior aquatic biologist, take flow measurements on the North Fork of the Poudre River in October 2018 to study potential impacts of the City of Fort Collins’ proposed Halligan Water Supply Project. Courtesy Colorado Parks and Wildlife by Mindy May

The group specifically thought that including more collaborators at the table earlier, particularly during the scoping and initial phases of the NEPA process, would make the permitting more meaningful by de-siloing and fostering collaboration from the get-go. The practice could also lead to better public comments, says Rob Harris, senior staff attorney for Western Resource Advocates, who was part of the lean group. “As a practitioner in the nonprofit world, my comments are stronger if I understand where the agency is coming from and I understand their concerns,” Harris says.

Many permitting processes, including those at the state level, require similar steps and studies, so under an efficient mechanism, agencies and project proponents can consider the various requirements together, Moyer says. That’s easier to do when stakeholders are brought together early; it can eliminate the necessity of re-doing studies based on the requests of an agency brought into the conversation later. The intent is to combine or run steps in parallel, rather than eliminate anything, Moyer says.

For example, CDPHE’s technical requirements and standards for 401 certification are more specific than those for the EIS, says Aimee Konowal, the Clean Water Program manager for CDPHE. If a project proponent does not know this in advance, they may collect data via one method for the EIS, then find that they must do it differently for the 401 certification.

“If you were looking at temperature impacts in a stream that the EIS may have looked at, there are different ways you can look at thresholds of what might be considered to be an impact to the stream,” Konowal says. “With the EIS process you have more flexibility as to how you set thresholds, whereas in [CDPHE’s] regulations, we specify specific methodologies and certain thresholds that our commission has adopted for that segment … The goal is always that the technical work is consistent in both processes and that we can use all of the technical work and documentation done previously for the EIS.”

It’s simple process tweaks, like getting informed about what different permitting processes require far in advance, that the lean method is trying to identify, Moyer says.

“When we talk about making the permitting process more efficient, I cannot stress enough that it’s not about lessening the analysis,” Moyer says. “The solutions hinge on how you engage stakeholders—you really need to have the right people at the right table early on in these water supply projects to seek agreement on methodologies, data needs and understanding impacts.”

However, early engagement could create its own problems, too. Project timelines may significantly shift under the One Federal Decision, says Stephanie Phippen, senior geoscientist and project manager for Tetra Tech, a water, infrastructure and environmental resources consulting and engineering firm. Since the clock starts with the publication of the Notice of Intent in the Federal Register, projects may now just complete more analysis up front before the notice, and before public input, in order to meet the two-year timeframe, Phippen says.

“Some speculate that projects may be further along and less open to change based on public input when they do finally publish the [notice of intent],” Phippen says. “If true, the end result could be that projects are front-loaded but overall take about the same time, and are less open to incorporating ideas brought forward by the public input. Time will tell!”

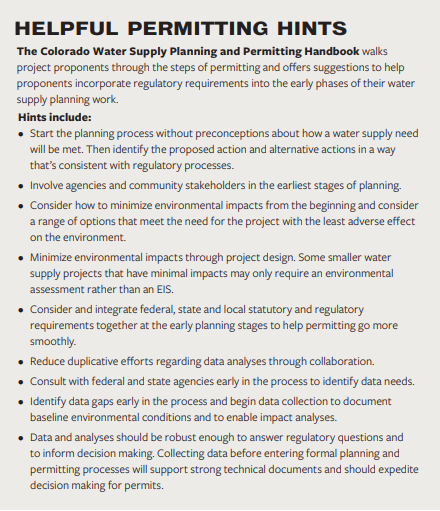

To put the lean lessons into action, the group developed a stakeholder engagement framework, interagency guidance documents, and the Colorado Water Supply Planning and Permitting Handbook. The handbook, released in October 2017, became the collaborative’s flagship item, Moyer says. The book is intended to be a resource for entities planning large water supply projects in Colorado and aims to help them incorporate local, state and federal regulatory requirements into initial water supply planning phases, long before they ever submit a permitting request. The handbook describes relevant regulations and their triggers; a timeline and details about efficiencies gained by integrating planning; and guidance on avoiding duplicitous assessment efforts. Now, Colorado officials are making an effort to promote the handbook and keeping an eye on new federal guidance for how it will impact the handbook’s recommendations, Moyer says.

Consultants for the proposed White River Storage Project are using the handbook as a reference as they navigate the early stages of building a dam and reservoir on the White River near Rangely to increase water storage during the frequent droughts experienced on the lower White River. The project began in 2014 and is in the initial phases of working through NEPA.

State staff recommended that the White River Storage Project staff take a look at the handbook; it provided some good general information but fell a little short on addressing some of the complexities associated with navigating the multiple internal permitting requirements at the state and federal levels, says project manager Brad McCloud with EIS Solutions. Nevertheless, the handbook helped give the team a different view of some of the goals the team was trying to accomplish: making their project as effective, efficient and streamlined as possible.

“Cost and timeline are always on your mind,” McCloud says.

One of the aftereffects of lean has been to help CDPHE get to the table earlier to build relationships with project proponents and federal and state agencies, Konowal says. In June 2017, the Colorado Department of Natural Resources and CDPHE signed a memorandum of understanding that represents a commitment by the agencies to work together on the Fish and Wildlife Mitigation Plan and 401 certification, when both entities are looking at impacts of a water project.

“A key piece for me has been working with Colorado Parks and Wildlife more closely on how do we not duplicate efforts,” Konowal says. “How do we move forward and have a comprehensive review, but make sure we’re touching base with each other and making sure that we’re being consistent with our regulations?”

Federally initiated processes

In addition to the One Federal Decision’s new two-year timeline, the 2017 executive order requires all federal authorizations for the construction of projects to be completed within 90 days of the issuance of a Record of Decision. In light of these changes, 12 federal agencies, including the Environmental Protection Agency, the Army Corps of Engineers and the Department of the Interior, signed a memorandum of understanding in April 2018 agreeing to cooperate on the timely processing of environmental reviews and authorization of decisions for proposed projects.

Harris, of Western Resource Advocates, finds the two-year timeline for completing environmental reviews problematic, and not just because he worries the One Federal Decision will diminish EPA’s role in reviewing, and potentially vetoing, permitting decisions under the Clean Water Act. “I think it’s going to be very difficult to craft an EIS that meets all the existing laws,” Harris says. “[NEPA, the Clean Water Act, the Endangered Species Act] … All those laws are basically intact. Their requirements are as strict as ever. And simply hurrying things up won’t necessarily result in more efficient decision making, but could result in lower-quality documents that are more susceptible to challenge in federal court.”

Nevertheless, Harris gets the desire for more efficient permitting. “I desire that, too—I want to see more focused, higher-quality analyses that really address the core conflicts. The documents spend a lot of time on stuff that’s not essential to the decision making.”

In 2012, the Obama Administration launched “A More Modern, Effective, and Efficient Federal Infrastructure Permitting Process,” a government-wide initiative to cut permitting decision-making timelines. The initiative created a committee whose duty was to coordinate and streamline agency reviews, it also designated senior officials as central points of accountability for meeting timelines, and made other changes as well.

There was also the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act, signed into law in December 2015; its 41st title was designed to improve the timeliness, predictability and transparency of the federal environmental review and authorization process for covered infrastructure projects. Project proponents can comply on a voluntary basis with FAST-41, which created a Federal Permitting Improvement Steering Council (FPISC) composed of agency Deputy Secretary-level members and chaired by a presidential appointee. FAST-41 also established new procedures for inter-agency coordination and communication, codified the use of the Permitting Dashboard to track project timelines and, importantly, gave agencies new authority to regulate the collection of fees, which would allow the FPISC to direct resources to the most critical functions within the inter-agency review process.

A ribbon-cutting ceremony celebrates the opening of the Watson Lake Fish Bypass in May 2019 at a diversion dam adjacent to Watson Lake and the Colorado Parks and Wildlife fish hatchery on the Poudre River. The bypass was built by participants of the Northern Integrated Supply Project, Morning Fresh Dairy, Noosa Yogurt, and Colorado Parks and Wildlife to improve habitat on the Poudre River and fulfills one of the promises made by NISP participants in the NISP Fish and Wildlife Mitigation and Enhancement Plan. Courtesy Northern Water

The process for redefining the project permitting regulations and guidance is still in flux. In June 2018, the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) requested public comment on potential ways to revise the NEPA process for better efficiency. The council has not yet made a determination; the CEQ has substantively amended its NEPA regulations only once since 1978.

The interactions between the executive order from the Trump administration and previous permitting reform attempts by the Obama administration are still a bit unclear, but it should be noted that streamlining permitting has been a goal for many previous administrations. The latest attempt by the Trump administration appears to have more teeth than those previous, due to its triggering of the inter-agency memorandum of understanding and the related changes to underlying laws such as NEPA and the Clean Water Act. However, like all executive orders, the One Federal Decision and its effects could be undone by the next administration.

However the rules shake out, project proponents hope to see a system that allows them to get the necessary work done, while hopefully avoiding a drawn-out process full of pitfalls.

“From the perspective of a group that’s working on a project that we feel very good about, anything that can help us get through the process and save on time and money … that’s our priority,” – Brad McCloud with EIS Solutions

“It really is exciting to see people working on the process, trying to make it better”, McCloud says.

Print

Print