In 2002, Colorado was rocked by a searing, record-breaking drought. The state, whose mountains had witnessed endless winter snows and huge spring melts for decades, went dry. Water was rationed. Cars weren’t washed. Lawns turned brown. Corn and alfalfa fields burned up.

In earlier droughts—in the late 1800s, the 1930s, the 1950s—Colorado was a sparsely populated place. Water decisions were made by a relatively small group of people: farmers, water utilities and large oil and mining companies, most of whom had staked their claims to the water decades ago. Few in the general public knew much about the intricate system of streams and irrigation ditches that funneled snowmelt from the mountains to the plains to the rivers that would eventually carry it far beyond our borders, to Los Angeles, El Paso, St. Louis and New Orleans.

Fewer still knew much about Colorado’s historical prior appropriation doctrine, a legal platform that dates back to the days of the gold rush. It was designed to allocate a scarce resource fairly and to prevent speculators from hoarding water. The doctrine says those with the oldest water rights have the first priority to use the water in a stream and that only those who can put it to beneficial use can divert it from streams or place it in storage. Hard-fought battles in the 1970s, 80s and 90s to expand the legal definition of beneficial use so that water could be kept in the stream for fish, kayak courses and riparian, or streamside, habitat were also known to only a handful of people.

These days, however, nearly a decade since that historic drought struck, the era of benign ignorance about one of Colorado’s greatest natural resources has ended. Coloradans know more about their water now than they ever have before. And a range of new water values is emerging. “These changed values are creeping in everywhere,” says Neil Grigg, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Colorado State University and the author of numerous books on water. “It’s subtle, but it’s almost like blood flowing through capillaries. It’s happening little by little, via different routes, and the result is big change.”

Coloradans are asking that water be used in new ways so that less is wasted, while critical water needs are met. Farm fields that once luxuriated in gushing floods of irrigation water are now carefully watered with sophisticated pipes that deliver precise amounts of liquid. Irrigation gates, once laboriously opened and closed by hand, are now operated mechanically using computerized remote controls so that adjustments related to changing stream conditions can be made quickly. Sophisticated moisture gauges tell growers how much water each plant should receive daily—information that is conveyed to computerized irrigation programs. High-powered irrigation wells that once freely pumped from aquifers are now closely tracked with meters, much like the meters that measure how much water a homeowner uses each day.

City dwellers too have dramatically changed the way they value water. Water rates have soared since 2002, and rate payers have demanded that this increasingly pricey commodity be used wisely. In Parker, residents have agreed to pay more to help fund a program that allows the city to use agricultural water from farms, but only in ways that allow the farms to keep operating. In Aurora, taxpayers have funded a groundbreaking water system that captures return flows in the South Platte that Aurora has already used, treats them through a series of settling ponds and filters, mixes them with purer mountain water the city has stored, and then delivers it to homes. The project, known as Prairie Waters, has won national recognition for its new water treatment methodologies and its efficiency.

“Prairie Waters is leading a wave of water supply in the West,” says Mark Pifher, former executive director of Aurora Water who recently left for Colorado Springs Utilities. “The West is becoming very urbanized. There is diminishing supply and a growing population. People are going to have to find a way to be more efficient with the supplies they currently have. They are not going to be able to wave a wand. So our ability to recapture and use what we have in a very efficient way is what all the major metro areas are going to wind up doing.”

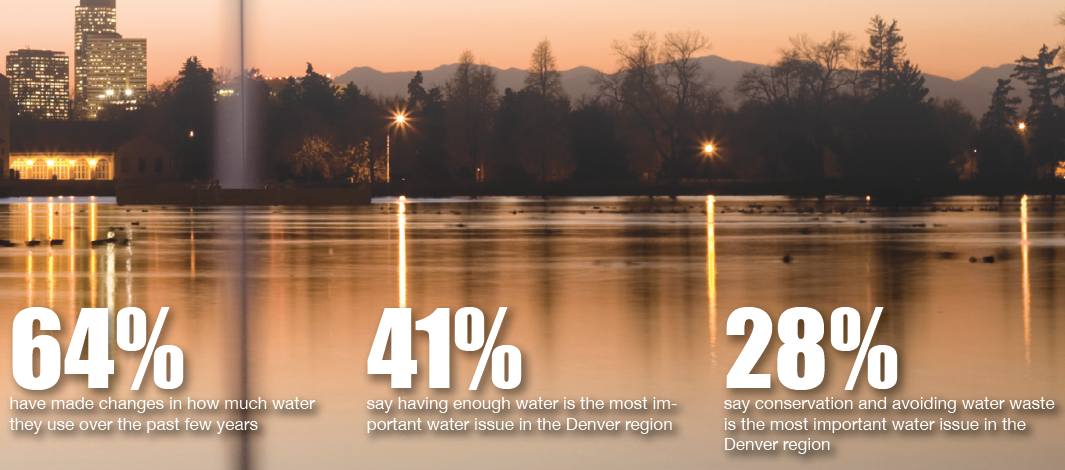

Denver Water, the state’s largest water utility, has tracked the attitudes and behaviors of its 1.3 million customers since the 2002 drought. “Surveys we’ve done have shown how our customers’ perspectives have changed,” says Denver Water’s manager of demand planning Greg Fisher. “People’s conservation ethic is easy to see. Their water use is 20 percent below where it was before the drought. It doesn’t matter that the drought is over. It truly is a new world.”

Like utilities everywhere, Denver Water carefully monitors use. One annual bellwether is the peak day demand. This is the one day each year—always a hot summer day—when Denver customers use the most water. In 1989, peak day demand stood at 550 million gallons. Last year, the peak day demand was 330 million gallons. “We haven’t gone over 400 in three years,” Fisher says. “Ten years ago people didn’t turn off their sprinklers when it rained. Now they do.”

People have also become deeply interested, almost obsessed, with water-saving toilets. Denver and other utilities offer rebates to homeowners who install ever more efficient devices. Once upon a time, a low-flow toilet that used 1.6 gallons per flush was considered cutting edge. Now, if Denver residents want a rebate, they have to purchase the 1.28-gallon version. Last fall, Denver Water asked the state legislature to mandate use of the 1.28-gallon toilets statewide. Turned down in this attempt, Fisher says the utility will make another run at the law in coming years in an effort to ensure that water savings continue to improve. “We’re not in a crisis right now,” Fisher says. “But the question is: Do you want to effect change in a crisis or do you want to effect change through leadership? We want to see what we can provide through leadership without waiting for another crisis to occur.”

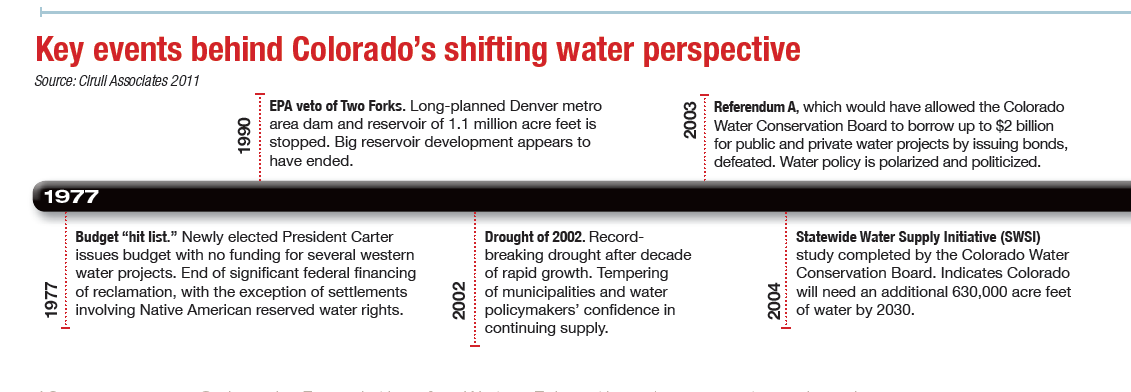

The 2002 drought has certainly had a profound impact on modern Colorado’s approach to water. But other earlier events set the stage for this era, where conservation is king, and streams, fish and kayakers have rights once reserved exclusively for farmers, miners and water utilities.

Pollster Floyd Ciruli’s grandfather grew melons in the Arkansas Valley. As a public opinion researcher, the Colorado native now makes his living taking the pulse of residents, conducting frequent polls on water. Ciruli says a number of historical events have transformed our beliefs about water. In 1977, for instance, President Carter stopped funding for federal reclamation projects. These projects were once the lifeblood of the American West, helping build some of Colorado’s largest storage facilities, such as the Aspinall Unit in Gunnison County and the Colorado- Big Thompson Project spanning from Grand County to the northern Front Range.

“At that point we realized there wasn’t going to be any more water from Washington,” Ciruli says. “Then we spent the next 13 years thinking about Two Forks.” Two Forks, proposed by south metro suburbs and Denver Water, was a 1.1 million acrefoot reservoir project, which was vetoed by the Environmental Protection Agency in 1990. “We had never before seen such a big project be stopped by environmental objections,” recalls Ciruli.

Other major shifts were also underway. Dick Stenzel worked for the Colorado Division of Water Resources for 25 years, serving as assistant state engineer and as division engineer for the South Platte Basin. Stenzel distinctly remembers the start of the legal battle over recreational water rights, in part because it occurred in Golden, a city whose streams he was responsible for regulating.

“Everybody knew the kayak courses existed, but for the most part, they basically used the river as it was. They never really filed for water rights,” Stenzel says. That started changing in the 1990s. The battle over whether a city could appropriate water for recreational use went all the way to the state Supreme Court. There, justices deadlocked in a 3-3 tie, leaving in place a lower water court’s decision to grant Golden the right to claim water for its kayak course, which was later affirmed by the state legislature. Since then, communities from Pueblo to Steamboat Springs to Durango and beyond have established kayak courses with guaranteed water rights.

Even streams now claim water for themselves. Since the mid-1970s, the Colorado Water Conservation Board has slowly, carefully acquired both new and existing water rights on streams throughout Colorado, in order to ensure some water remains for the benefit of fish and aquatic habitat. The Colorado Water Trust, an innovative nonprofit created to bolster the state’s efforts, is doing the same, identifying water rights holders who are willing to donate, sell or lease some of their water so that it can instead be kept in rivers.

In the mountains and even downtown Denver, dozens of watershed groups, funded by the Environmental Protection Agency and the occasional bake sale, carefully monitor the streams in their communities, engaging with kayakers, farmers, scientists and local water districts to measure everything from heavy metals to stream temperatures. Their dedication and careful work has supplied the state and federal government with more local stream data than ever before and, as a result, these agencies keep much better track of stream conditions themselves.

In 1989, the year the Colorado Watershed Assembly was founded to support and connect watershed groups across the state, only a handful of such groups existed. Now the assembly has nearly 80 member organizations statewide, organizations with access to a small, but steady source of grant-based funds from fellow Coloradans, who can donate by checking a box on the Colorado Income Tax Form. The donation program, known as the Colorado Healthy Rivers Fund, is administered by the Colorado Water Conservation Board. The CWCB reviews grant applications from both watershed groups and others seeking funds for projects to benefit waterways. Since the income tax check-off began in 2003, 105,000 Coloradans have donated $816,000.

“In some ways Colorado has always been a natural resource investment kind of state,” Ciruli says. “Water diversion, water development… it’s always been part of the culture. During the 1990s and early 2000s, though, there was all of this massive growth and there was decline in the public consciousness about water. But that changed in 2002. The drought really got deep into the soul of the public and water planners.”

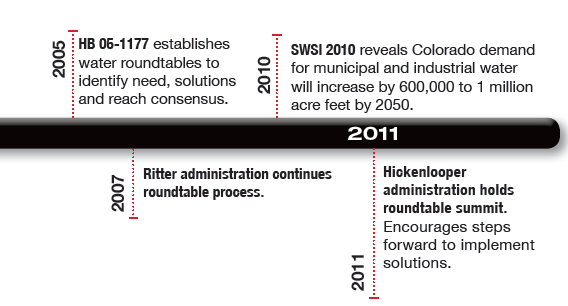

And the mark it left isn’t likely to fade, thanks in part to changes in the way water policy is made. Russell George, former director of the Colorado Department of Natural Resources, saw the bitter conflict the drought precipitated and sought ways to bring people together for public dialogues over how water in their communities should be stored and distributed. The result was the establishment of public roundtables in each of the state’s river basins. A super-body known as the Interbasin Compact Committee (IBCC) was also created to facilitate discussions between the roundtables. Suddenly, water discussions are as much a part of community life as a county commission meeting.

“Water is becoming a much more public discussion,” agrees Denver Water’s Fisher. It’s also becoming more collaborative. Last year Denver Water reached a groundbreaking agreement with numerous West Slope parties, conceding to sharply limit any water it takes from Colorado River Basin streams in the future in exchange for support to expand Gross Reservoir in Boulder County. Denver and Aurora have also partnered to expand the use of the Prairie Water plant so that water-short communities in Douglas County, to the south, can tap some of Denver’s return flows instead of seeking new supplies from already-stressed West Slope rivers.

CSU’s Grigg says these shifts in the public’s perception of water and how it’s valued are likely to bring good things to the state. “I don’t see any downside,” Grigg says.

Print

Print