listen to the story

Wastewater and municipal sewer systems around the country are dealing with a growing problem—people are putting things down the drain and down the toilet that are playing havoc with the system. As Maeve Conran reports in our ongoing radio series on water issues, Connecting the Drops, several Colorado municipalities have launched public awareness campaigns on what not to put down the drain.

The sound and smell of bacon frying is a pretty common occurrence in households on weekend mornings. Now imagine this happening in millions of households around the state and then imagine the cumulative effect of all those greasy frying pans getting washed. It’s something Liam Cavanaugh, director of operations for Metro Wastewater Reclamation District thinks about frequently.

“If you think about 2 million people worth of wastewater, that’s a lot of wastewater and so if every household is dumping their bacon grease down the drain on a Sunday morning, that can cause a lot of problems in the piping here at the treatment system.”

Metro Wastewater Reclamation District treats the wastewater of about 2 million people in the Denver area. The Robert W. Hite plant close to downtown Denver deals with the bulk of it. Pretty much anything that goes down the drain in this area comes straight here to be treated, cleaned and ultimately discharged back into the South Platte.

“What you’re looking at here is about right now 100 million gallons per day of wastewater flow coming in. And this what we’re looking at is mainly from areas in Denver and south and west of the Denver central area. We also have another flow over here that you can see that comes from Aurora, Denver International Airport and areas north and east of this facility. So we have two different influent streams and we run two parallel treatment processes here at the facility and then we go through those processes and eventually combine for our effluent that recharges the South Platte River.”

This treatment plant is able to handle the usual suspects that get sent down drains and toilets in a busy urban area like this, but they’re encountering a growing trend that is causing problems with the system. Fats, oils and grease or FOG. And it’s becoming a major issue for municipalities around the world sometimes leading situations like the one in London in 2017 when a 130-ton mass of cooking fat and sanitary products clogged the sewers under the city. It was one of the world’s largest fatbergs.

While Denver hasn’t experienced anything close to this scale, FOG has become a big enough issue for entities like Metro Waste Water to launch a public awareness campaign. Fort Collins is another municipality dealing with the issue. Last year they launched their own campaign letting people know that FOG can clog. Andrew Gingerich, director of water field operations for the City of Fort Collins Utilities says it’s not just FOG that’s an issue.

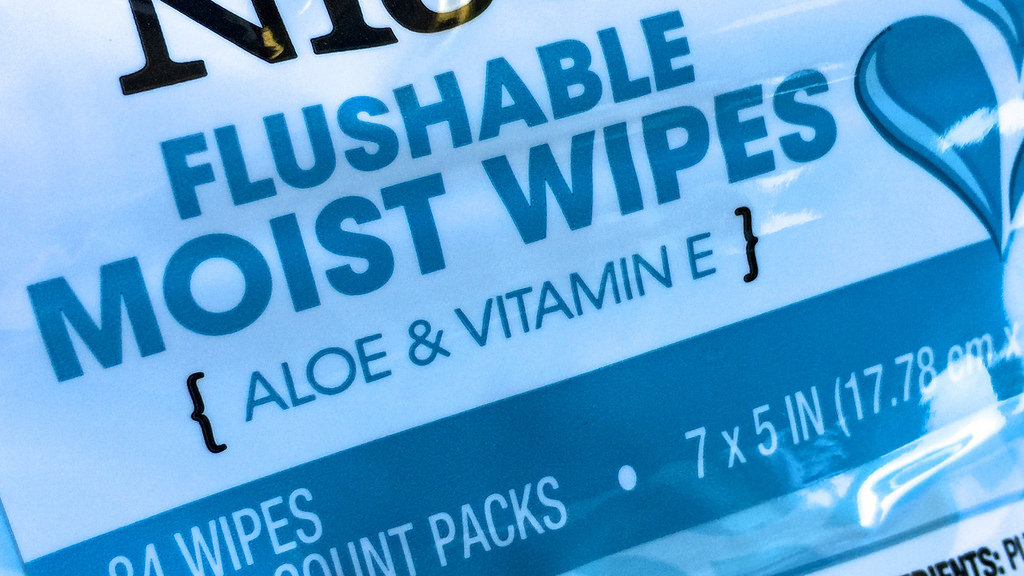

“We do find a lot of flushable wipes in our system and it is one of the leading causes to backups that we have, along with fats, oils and greases. And then there’s other things that get flushed but I’d say the flushable wipes and the fats, oils and greases are the main contributors to the backups that we see and the reason for our aggressive cleaning of our pipes.”

Those flushable wipes are not so flushable and they’re becoming an increasingly large problem for communities around the world. In 2015, personal wet-wipe sales reached an estimated $2.2 billion and sales continue to grow. But while they’re marketed as flushable, they don’t biodegrade like toilet paper. When they’re combined with fats, oils and grease is when the real problems start.

“Once you start to get that impediment, then more grease is gonna stick to that grease and that’s how you start to develop the fatberg. Then once that starts to impede flow, then other solids will start to stick. Wipes, cue tips, all that debris starts to build and it’s a big solid block. I’ve heard stories of our operators pulling what they thought was a cement parking block out of a sewer, ‘cause it looked like cement, and it was actually a big congealed log of grease that had just built up over the years.”

Gingerich says that while restaurants should have a grease catchment system to avert it from the drain, the general public may be unaware of the impact of what they’re doing.

“The issue with grease is that typically when grease is poured down the drain it’s hot and so it looks like it’s just gonna go down the drain but when it comes in contact with that other water either in your home or once it gets to our system that water is not as hot and then that grease will start to congeal and then it’ll stick to our pipes.

So here’s a quick rundown of what you can and cannot put down your drain or toilet.

Q tips…NO

Dental floss: NO

Flushable Wipes: NO

Dead goldfish: Never!

Fats, oils and grease: Definitely NO

Toilet Paper: YES

Toilet paper, pee and poop are the only things that should be flushed. And what should you put down your drain? No solids, including fats that will solidify. Instead, scrape oil and grease out of frying pans into a container such as a tin can and dispose of it.

The Robert W. Hite treatment facility near Denver is a stark reminder of why we need to be aware of what we’re pouring down the drain or flushing down the toilet. Here at the end of the treatment process the water, now treated and disinfected, is discharged back into the South Platte River on its way to another user downstream.

Liam Cavanaugh, director of operations for Metro Wastewater, says that while people might not give a second thought to the water that goes down their drain or toilet, we really should all pay closer attention to it. Particularly as the water being discharged here makes up more than 85 percent of the South Platte River flow from this point on.

“It’s not just a sewer that dumps into the river, there really are downstream consequences from putting things down your drain that can impact our operations and ultimately impact water quality in the river.”

Connecting the Drops is produced in partnership between Water Education Colorado and Rocky Mountain Community Radio stations. This series would not be possible without the generous support of CoBank, a national cooperative bank helping to provide financing solutions for rural water systems.

Print

Print