Nearly $86 million in federal funding to help small Colorado communities with the daunting task of removing so-called “forever chemicals” from their drinking water systems will begin flowing this spring, but whether it will go far enough to do all the cleanup work remains unclear.

Small Colorado communities are scrambling to find ways to remove the toxic PFAS compounds that wash into water from such things as Teflon, firefighting foam and waterproof cosmetics.

Thanks to the infusion of federal money this year, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment is offering what are known as small and disadvantaged community grants to help with cleanup costs.

Around the country, the EPA is racing to help communities that have historically been left out of national funding initiatives, according to Betsy Southerland, a scientist with the Environmental Protection Network, a nonprofit that advises communities nationwide on the scientific and technical issues inherent in treating water quality problems.

“This is a massive effort,” Southerland said, likening it to the nation’s $15 billion-plus effort under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to identify and remove aging lead pipes from drinking water delivery systems.

Hundreds of communities in Colorado, large and small, are monitoring for PFAS, and some are planning costly new treatment plants to address the issue.

Greeley, which is eligible for the new grant program, has yet to detect PFAS contaminants in its treated water because much of its current water supply flows down from the headwaters of the Upper Colorado River and is relatively clean. But the fast-growing city is also planning to develop new groundwater supplies and is therefore planning a new treatment plant capable of addressing any future contamination should it occur, according to Michaela Jackson, Greeley’s water quality and regulatory compliance manager.

Colorado lawmakers are also working on new legislation to address the widespread contamination.

Still, word of the Emerging Contaminants in Small and Disadvantaged Communities Grant Program, as it is known, has been slow to spread, Colorado public health officials said, in part because the problem is still being understood and remedies are still being studied.

“Emerging contaminant funding is relatively new. Many communities are still determining if they have a project they may need to request funding for,” state health department spokesman John Michael said in an email.

Just four communities have applied to date: South Adams Water and Sanitation District in Commerce City; City of La Junta; Louviers Water and Sanitation District in Douglas County; and the Wigwam Mutual Water Company in Fountain.

Each year for the next five years, the state will offer two rounds of grants, with millions of dollars committed. Communities interested in applying can explore the program here. The next grant cycle opens in July, according to Michael.

This year, perhaps as soon as this month, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is expected to finalize the first PFAS drinking water treatment standard, which will require utilities to remove the contaminant at levels above 4 parts per trillion.

Prior to this, the federal oversight of the contaminants was advisory, meaning utilities were not technically required to remove it, according to state health officials. The advisory rule was set at 70 parts per trillion.

Still, most water providers have been testing and monitoring for the compounds for several years, and where contamination that exceeds federal advisory guidelines has been found, many have instituted efforts to filter the toxins out and bring in new sources of cleaner water to dilute any remaining contamination.

But for small communities lacking such resources, the costs and stakes are high.

Searching for millions of dollars more

The South Adams County Water and Sanitation District, which serves Commerce City and unincorporated parts of Adams County, has been hard-hit by PFAS contamination in its groundwater wells. Where the toxins have come from isn’t entirely known, but could include firefighting foam used nearby at a firefighting academy owned by the City of Denver.

When PFAS was first detected in 2018, the Adams County district had to shut down its most contaminated wells, build an expensive system of filters, and buy water from Denver to dilute its water sources enough so that PFAS could no longer be detected.

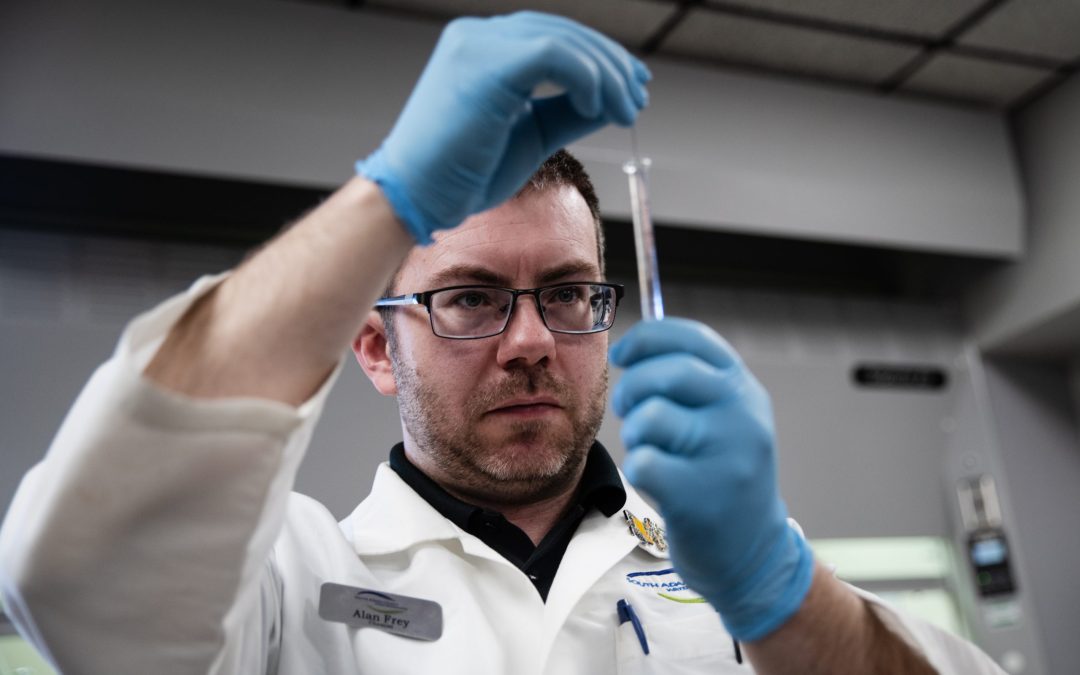

It also built a cutting-edge testing lab, so that it can know within 24 hours whether its extensive treatment system is working and respond immediately if it is not.

But that isn’t enough. This year it will begin building a new $80 million treatment plant, $30 million of which will come from the new state grant program. It has also been approved for a special $30 million loan from the Colorado Water and Power Development Authority. It is still pursuing additional funding to minimize the amount it will have to seek from its customers to help cover the costs, according to Abel Moreno, the district’s manager.

“It’s absolutely critical that we find another source of funding because we don’t believe the contamination was caused by our rate payers, and we do not believe they should be asked to pay for it,” Moreno said.

And it’s not just initial construction costs for treatment systems that will need funding. Operating the systems and disposing of contaminated treatment equipment can cost millions of dollars as well, according to the American Water Works Association, which has been critical of the pending federal standard because it believes it will cost utilities and ratepayers too much money. It has advocated a lower treatment standard, of 10 parts per trillion.

The 4 parts per trillion standard will require “more than $40 billion of capital investment plus significant investment for operation and maintenance,” said Chris Moody, regulatory technical manager at the association, in an email. “The annual impact to communities and ratepayers is expected to exceed $3.8 billion, increasing household water rates by as much as $3,500 annually.”

But utilities such as the South Adams Water and Sanitation District believe there is no choice but to power ahead with the PFAS cleanup.

Decades of living near industrial producers and the Rocky Mountain Arsenal Superfund Site, and historic concern over the safety of its drinking water, have created a deep distrust among residents. Moreno says the district is working to rebuild faith in its water system.

“It is a priority of mine to change the trajectory of the district’s water image so the people we serve in this community have confidence in the work we’re doing and the water we are producing,” he said.

Print

Print