One of our board members, Peter Ortego, shares knowledge and insight gathered from a career in law, most recently and extensively as the director of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe’s Department of Justice. The tribe is located in the Southwest corner of Colorado, headquartered in Towaoc, Colo., and has some acreage in New Mexico and Utah as well. In his role with the tribe, Peter protects the tribe’s water rights and their relations with the local and federal governments. He is proud of his part in negotiating and drafting the construction contracts in the Animas-La Plata (A-LP) Project, as well as his role in maintaining and further developing it today. The tribe’s main water projects and sources are McPhee Reservoir by Dolores, Colo., part of the Dolores Project; Lake Nighthorse by Durango, Colo.; and Mancos Creek in Montezuma County, Colo. Peter has been serving on the WEco Board for 1.5 years. We spoke with him to learn more about tribal water rights, featured in our Spring 2022 issue of Headwaters magazine focused on tribal water.

How did the Colorado Ute Indian Water Rights Settlement Act of 1988 affect the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe? (The 1988 act affirms the Utes’ rights to surface streams and tributary groundwater on the reservation. After decades of planning, amendments in 2000 allowed for the construction of the Animas- La Plata project).

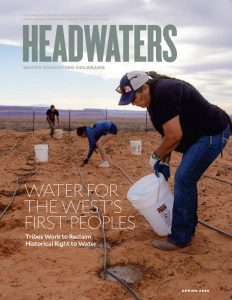

Even as late as the ’90s, the tribal members here in Towaoc were hauling their water. They used to tell me anecdotally about how they’d wait for the water truck to come and they’d be all excited about filling up their tanks to turn on their pumps to have water. Then, we did the McPhee Project [McPhee Reservoir is part of the Dolores Project], which is currently bringing water to the reservation. People can just go turn on their tap. Now they’re getting clean water that’s been treated by the City of Cortez. It is bringing really great health benefits from convenience to quality of life which has gone up insurmountably.

Secondly, there is the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe Farm and Ranch Enterprise, which I believe is the largest farm in Colorado and it’s one of the more sophisticated farms in the nation. They’re an amazing operation that’s been able to employ and train tribal members. That’s been able to bring some revenue to the tribe and the people that work there really enjoy it. The farm supplies food for tribal members; they can get free corn and hay from the farm for their cattle. The farm’s cattle operation is possible because the [Dolores] project was able to bring those kinds of resources to the tribe.

Another aspect about water that I can’t ignore when talking about Native Americans and specifically in reference to the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, is a real spiritual connection to water. There’s a Ute word for it, that I don’t even try to pronounce, but there’s this notion that the world is sacred and needs to be protected and respected. One of those sacred resources for the Ute people is water. They prefer to let water flow naturally, where Mother Nature intended, instead of building reservoirs, dams, and canals. The tribe holds water very sacred and they value what the water does for them, not just personally for their own health and welfare, but for the birds, animals and plants. To respect water as a resource is a high priority and value to them.

When they were building Lake Nighthorse, there was an interesting issue. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation put aside 4% of its total funding for cultural resource mitigation. That basin is in a very culturally rich valley. For thousands of years, people have been occupying that basin, so when Reclamation was doing the cultural resource mitigation, they came across ancient burials. Reclamation and the tribes involved did the best they could to mitigate those discoveries, but not everything was removed. Reclamation does not show records of this and I’m not sure why, but there is still, to this day, a burial underneath Lake Nighthorse. The tribe is concerned that unless we pay proper homage and proper reverence to those burials, Lake Nighthorse could end up being a problem for the people of Durango, for the tribes, and for anybody who utilizes the water out of that lake. It’s a notion of respecting the ancestors, who are still there and so that’s a really interesting cultural dynamic. I know all the partners in the project are sensitive to that and everybody’s tried, in one way or another, both to enhance development of the lake either through recreation or other means, and yet still pay respect. Maybe we’re not all in agreement as to exactly how to do that, but I do believe that everybody involved in that project is sensitive to that problem and they want to pay reverence to the people there. That is an interesting dynamic, not just with the sacredness of water, but the impacts of moving it into unnatural places. So what has it brought to the tribe? It’s brought positives and it’s brought concerns.

What are some of the difficulties you have faced and are still facing with the Animas- La Plata project and general water access on the reservation in terms of water rights or infrastructure?

We’re part of the La Plata West Water Association which was developed so that private interests and other interests can build pipelines to bring the water west from Lake Nighthorse sort of over the hill, so to speak, and into La Plata Valley. When A-LP was first constructed, it was a much larger project and it was intended to send a lot of water to the irrigators in the La Plata Valley. However, now it’s only municipal and industrial water; there’s no longer an irrigation component to the project. It’s been downsized quite a bit. One of the aspects of the downsizing is that in the beginning, they envisioned not just infrastructure to deliver irrigation water to the La Plata Valley, but to deliver drinking water, all the way to Towaoc. That would have been a robust project, covering many miles, so once that component of the project was gone, we started working with La Plata West Water Association to develop infrastructure to get domestic water to the reservation. It’s a slow and expensive process, but we are part of that process. The water leaves Colorado down the Animas River, so we have 16,000 acre-feet that leaves Colorado on the Animas River and it goes into New Mexico where it hits the San Juan River. Then, the San Juan River comes back up and crosses into Colorado for only about a mile and that’s on reservation land. So, there is a way that Animas-La Plata water can get all the way to the southwestern end of the reservation. However, in order to do that it’s pretty complicated. As you can imagine, the State of New Mexico would have to be involved and probably the State of Colorado would have to be involved in one way or another, so there’s some pretty complicated negotiations, particularly right now with droughts going on.

Also, we’re using all of our water allocation out of McPhee and there is still a need for additional water, mainly because of drought. The tribe was told that its water allocation out of McPhee would only be 10% this year for the farm, so that’s really alarming. I would like to think that McPhee supplies all the water that the tribe needs in Colorado but it’s really just not true. We have another reservoir that we want to try to fill that’s in the southern end of the reservation and that would get filled by the Mancos river. The Mancos is another river that eventually flows into the San Juan, but it’s fed by Jackson Reservoir which is above Mancos. The Mancos Conservation District has done a terrific job of piping that water to be the most efficient they can be with it. They’re doing things like salinity control, and those efforts have benefited the tribe because the tribe is at the bottom end of that system. If they have a clean and efficient system, then there will be more clean water coming on to the reservation through the Mancos River. The tribe has some protective wetlands along the Mancos River. We always try to improve water quality and protect the species that are in the river, but we also have the Mancos Reservoir that we’d like to fill to help our ranching. On the reservation, there is still that need for water.

As far as senior water rights go, the tribe’s senior water rights have not all been developed because it’s very difficult to do. Probably the most senior water rights that we have are the ones over by Lake Nighthorse and we’re working on that infrastructure to get it over to the reservation. We’re also seeing how we can use water passing through New Mexico, but it’s been very difficult to get access to that water. The tribe took a lower senior right in the Mancos River in order to get this project done. So it really doesn’t have any senior water rights right now that it’s ignoring. The tribe is trying to use the senior water rights over in A-LP and eventually when it does make a New Mexico settlement, that’ll be a senior water right. So those are the efforts we’re making to use our senior water rights right now.

Why are Ute Mountain Ute Tribe water issues important for our widespread readership to know about?

Recently, tribal water has taken on a greater significance in the Colorado River. I think everybody’s been aware of the role that the tribes play in the Colorado River. Tribal water rights in the Colorado River make up about 25% of all the water in the Colorado River. Everyone has a reasonable fear about what to do if the tribes were to start using all of their water because there would be a lot less in the Colorado River to deliver to Lake Powell. I think it’s useful for the tribes to be a part of the discussion on how we manage the Colorado River. One of the ways that Ute Mountain is involved in those discussions is they’re not only a part of the Ten Tribes Partnership, but we’re also negotiating our water rights in New Mexico because we have 104,000 acres down there, but right now we have no water rights. The state of New Mexico has been adjudicating the water right on the San Juan River now, for what seems like 40 or 50 years to me. We have been engaged with New Mexico and Colorado and the Ten Tribes Partnership to figure out holistically, how A-LP water plays into this. If the tribe is going to be settling a New Mexico water right, it wants that water right to be in addition to any other water right. But as we’re talking about maybe using tribal water to solve part of the problem at Lake Powell and Lake Mead, there’s going to need to be a way for us to be able to move our water through New Mexico and then through Utah and then to get it into Lake Powell. Our water rights negotiations in New Mexico, are not ignorant to that particular need in that particular function for survivability of the river so we’re involved with that.

We are also going to pursue water rights in Utah for the White Mesa community. I mention the White Mesa Uranium Mill because that’s part of the urgency for us to solve the water problem in Utah. The White Mesa Uranium Mill is about three miles north of the White Mesa community, and, in our opinion, it is causing a lot of pollution to the water aquifer that supports the White Mesa community, the Navajo Nation, and the town of Bluff, which are all south of and down gradient from the mill. Directly under the mill, there are two aquifers: the shallow aquifer and a deep aquifer. I don’t believe anyone is taking drinking water out of the shallow aquifer, but we’ve already identified contamination in that aquifer. We’re afraid that it’s only a matter of time before that contamination reaches the deeper aquifer. I have heard from many people, although I haven’t seen the science for this, that those aquifers do eventually reach the Colorado River. So it’s not just important to the tribes, and the people in Bluff to preserve their drinking water, but this could become an entire upper basin and lower basin issue. At some point, if in fact the contamination from the White Mesa Mill water reaches the lower aquifer and then eventually makes its way into the Colorado River, then uranium contamination will be a problem. That wouldn’t happen tomorrow or even next year. It would happen a long time from now, but we do have to think in terms of dozens, hundreds, or even sometimes thousands of years. It’s really difficult for us to wrap our brains around what’s going to happen in 1,000 years, so we tend to keep it in the context of smaller periods of time, but that’s really important to try and conceptualize. We need to start to solve the water problem for the people in White Mesa and we’re initiating that now.

What are some of the projects and negotiations you hope to achieve in the future

We’re working with the Dolores Water Conservancy District to put in a series of turbines that will generate power with the pressurized water coming from McPhee to the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe Farm and Ranch Enterprise. Right now there is an energy dissipation structure, a couple million tons of cement, that slows the pounding water coming out of the siphon. So the tribe is also trying to use water, not just for drinking for irrigation but we’re also trying to utilize it for energy production.

We also want to achieve “Treatment as State” (TAS) for our air quality like we have for our water. The treatment as a state is great. With the Clean Water Act, tribes are allowed to receive treatment as a state, which means they get to dictate or regulate the quality of the water that’s on the reservation and that enters the reservation. We do have our standards set now, but not having enforcement is a little bit of an issue. It’s something we need to think about and fix. The main issue for us really is oil and gas operations. The tribe has a lot of oil and gas operations on the reservation and oil operations in particular can be very messy and a spill can very easily get into a waterway and affect downstream systems. We do need to start working on the enforcement capacity of it, but just having those standards allows us to get funding for the monitoring. It allows us to put resources towards ensuring that the water is clean, even if we’re not fining somebody or going after somebody, we still have the ability to utilize technology and other things, to make sure that the water is good for the reservation. Having the TAS contributes to our ability to regulate the quality of our own water.

What concerns do you have for the future, especially with climate change and drought.

I’d hate to see our farms turned to dust. I’d hate to see any farm around here turn to dust. Another one of my concerns is over in White Mesa, with the Wenuche people, and the ghost towns all over Allen Canyon. I worry about what’s happening in Utah with climate change because that entire area gets its water out of one reservoir- Recapture Reservoir. I don’t know if it is going to be able to continue to meet the needs of all the people. I worry about how the United States might do something to tribal water, using eminent domain, and also whether that water is going to be available at all. For the people, particularly in White Mesa in the future, it’s not a question of what they do, it is what we do as a nation to protect them and to honor the commitments we’ve made to the Ute people. We need to start thinking about solutions to these kinds of problems. I hope they never arise, but we don’t want to be caught flat footed if they ever do arrive.

Read more about tribal water in the spring 2022 issue of Headwaters magazine.

Read more about tribal water in the spring 2022 issue of Headwaters magazine.

Print

Print