Photo Credit: USDA

In 2012, city officials in Flint, Michigan, began to investigate the possibility of saving money by switching water providers. Projecting a savings of $200 million over the course of 25 years, they decided to build their own pipeline to the Karegnondi Water Authority (KWA) instead of continuing to receive water from Detroit Water and Sewerage Department (DWSD). Officials then searched for an additional water source to bridge the gap between the loss of water being provided by DWSD and the completion of their connection to KWA.

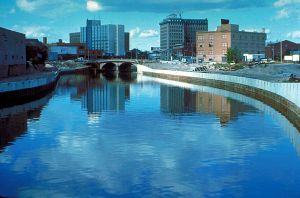

Flint River

They settled on using the Flint River.

On April 25, 2014, Flint—a city where 40 percent of its people live in poverty—began drawing water from the Flint River for public use. Officials did not implement corrosion control treatment at the Flint Water Treatment Plant—a standard practice that prevents supply pipes from leaching lead. Shortly after switching the water supply, residents complained about water quality, but it was not until early 2015 that city tests verified what people had suspected—levels of lead in Flint’s drinking water exceeded U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) standards. An independent test done by Virginia Tech found lead levels at 13,000 parts per billion (ppb). The EPA limit for led in drinking water is 15 ppb and water is considered hazardous waste at 5,000 ppb.

Photo Credit: Ildar Sagdejev

The decisions officials made in Flint brought to light the environmental struggles faced by poor, rural and underserved communities across the nation, forever changing the perception of public drinking water, and prompting people to ask one very pertinent question that they had not previously considered:

How do I know if my drinking water is safe?

On November 30, 2016, EPA published the results of its six month review of the nation’s drinking water strategy in their report, Drinking Water Action Plan. This plan includes six priority areas, along with recommended actions to improve water quality and health in the United States.

On November 30, 2016, EPA published the results of its six month review of the nation’s drinking water strategy in their report, Drinking Water Action Plan. This plan includes six priority areas, along with recommended actions to improve water quality and health in the United States.

The six priority areas are:

- Drinking water infrastructure financing and management in low-income, small and environmental justice communities

- Oversight for the Safe Drinking Water Act

- Strengthening the protection of water sources

- Addressing unregulated contaminants

- Improving overall transparency, public information and risk communication

- Reducing lead risks

Photo Credit Steve Johnson

Circle of Blue, an online news source affiliated with the Pacific Institute and founded by journalists and scientists who conduct data analysis and document emerging and recognized crises, states that approximately 27 million Americans are served by public water utilities that are in violation of federal drinking water standards. Millions more draw their drinking water from unregulated, contaminated, household wells. And while 99 percent of Americans have access to an improved water source, underserved communities sometimes receive water from sources that present a health hazard.

These priority areas and actions for improvement would have an impact on Colorado’s rural water supplies, which have seen their own fair share of struggles when it comes to ensuring that the water is safe and free from contaminants. Headwaters magazine article, “The Rural Water Conundrum,” speaks to that exact issue. According to the article, 98 percent of Colorado’s water systems serve communities smaller than 10,000 people. These small communities could benefit from the improved support outlined in EPA’s new action plan.

Implementing change will not only require billions of dollars to be spent in order to update inefficient and outdated infrastructure, but will also call for the cooperation of government officials, water utility services and the public. Currently, the future of the Drinking Water Action Plan is in question, and only as time passes will we know if EPA’s suggestions will take shape in the form of solid action.

Until then, the public will continue to ask: Is my drinking water safe?

Knowing what is in your water and how policy makers can impact public health is the first step being able to make decisions that will have a positive impact on your personal well-being. Read more about water and its connection to public health in the latest issue of Headwaters magazine, Renewing Trust in the Safety of Public Water.

Knowing what is in your water and how policy makers can impact public health is the first step being able to make decisions that will have a positive impact on your personal well-being. Read more about water and its connection to public health in the latest issue of Headwaters magazine, Renewing Trust in the Safety of Public Water.

Not a Headwaters subscriber? Visit yourwatercolorado.org for the digital version. Headwaters is the flagship publication of the Colorado Foundation for Water Education and covers current events, trends and opportunities in Colorado water.

Print

Print

Reblogged this on Coyote Gulch.